Modern Japanese science fiction was birthed in nuclear fire at the close of World War II.

It left a sobering impression of the dangers of technology that can be felt to this day, and it created a generation of directors who are keenly aware of how delicate their mortality is. Science fiction is a medium of escapism that can easily serve as a form of cultural criticism or rebellion, and it was rich soil for these artists.

One thing that did change over the course of this period was the relationship between the public and the government. Earlier films were more willing to depict the government in a heroic light in the face of forces beyond human understanding. By contrast more recent movies often depict authority figures as corrupt or incompetent, with an individual hero needing to break the rules in order to save the day.

Above: Japan’s history of Science Fiction depicts new worlds and counter-cultural politics.

Intended as a metaphor for Nuclear devastation, Godzilla was anything but a joke.

The progenitor of the Kaiju movie subgenre, Ishiro Honda’s “Godzilla” (Gojira in Japan) has far-reaching cultural influences both in Japan and beyond. With 31 films in its franchise, two of which are American remakes, and an animated series from 1998, Godzilla has become a household name all over the world. There isn’t really a consistent tone to these movies though, with many made to be campy summer popcorn flicks of giant monsters fighting each other in special effects-laden battles.

This could not be further from the truth for the 1954 original film. It was created less than a decade after the atomic bombs “Fat Man” and “Little Boy” were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II, and the aftershock of their blast is palpable here. Godzilla was a reflection of the dangers of nuclear weapons, and despite only being on screen for about eight minutes of the film’s total run-time the monster’s devastation is given weight due to the film carefully developing its human characters. The titular prehistoric monster is awakened by the bombs that were dropped on Japan. The film steers away from an anti-American message, instead focusing on the potential dangers of nuclear testing.

“The H-Man” took the effects of radiation poisoning and made them into a monster.

The H-Man

Another project from the creative team behind “Godzilla,” “The H-Man” (“Beauty and the Liquid Man” in Japan) also bears the mark of atomic fire visible in many films of the era. Where their previous film served as a warning of the potential dangers of nuclear weapon testing, “The H-Man” seems to focus more on the dangers of radiation. The H-Man are a race of green slime creatures who dissolve any human that they come into contact with. The story shifts tones throughout its run-time, beginning as an isolated horror/thriller, then veering into a noir detective story before morphing into a city-wide disaster film.

“The H-Man” was an at least partial attempt at making an American-style gangster movie. It begins as a story about a disappearing drug-dealer, and just as “Godzilla” before it used it’s special effects sparingly, the titular monsters do not appear in person until the movie is well underway. At this point the story shifts from “The Maltese Falcon” to “The Blob” as the police and the government attempt to defeat an enemy who cannot be harmed by conventional means, but that can rot them away with a touch.

The story does bare some changes between the Japanese and American releases. “The H-Man” ends on narration that explicitly cautions against nuclear testing, while the original Japanese cut of the film conveys its anti-nuke message more subtly.

Gamera, the Guardian of the Universe, could be set to make a big-screen return one day.

Gamera

Originally conceived as a rival franchise to Toho’s internationally successful “Godzilla,” the flying turtle-like “Gamera” did not receive the same level of acclaim. In the original film, Gamera is awakened from its prehistoric slumber due to a conflict between American and USSR fighter jets. The beast puffs fire and guzzles petroleum for fuel, and while he does rampage and destroy cities it is also made clear that Gamera is not inherently evil. He even goes out of his way to protect a human child from danger, eventually earning him the moniker “friend to all children.”

“Gamera” lacks the clear anti-nuclear weapon message of “Godzilla,” and this monster tends to be benevolent towards humans rather than a destructive force of nature. Many of the sequels feature Gamera protecting humanity from other giant monsters, where Godzilla is an antagonist as often as not. Despite his decades-long franchise, Gamera’s most recent film came out more than ten years ago now.

However, the recent success of films like “Pacific Rim” and “Godzilla” have shown that there is still a market for Kaiju movies. Enterprising director Katsuhito Ishii created a short trailer as proof of concept for a new film. The trailer was revealed at New York Comic-con in 2015 to positive feedback, but despite this the new project has yet to be greenlit.

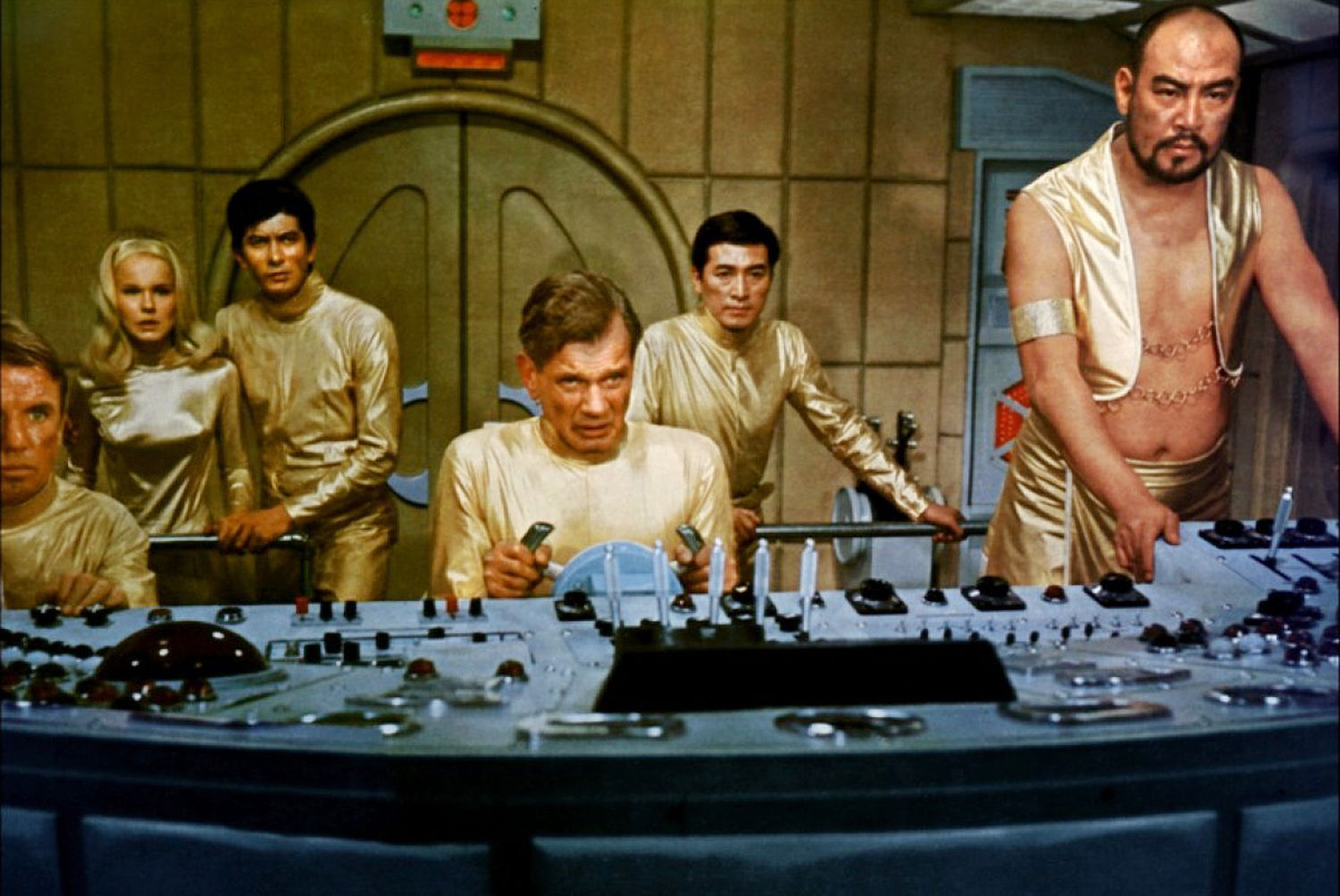

“Goldfinger” meets Jules Vern in “Latitude Zero.”

Latitude Zero

Another project from Toho’s Ishiro Honda and Eiji Tsurubaya, “Latitude Zero” is a science fiction adventure in the same vein as “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” and “Star Trek: The Original Series.” The story begins when two scientists and a photojournalist are trapped underwater in a bathysphere due to volcanic activity. The trio is rescued by Captain Craig Mackenzie in his submarine Alpha. Captain Mackenzie brings them with him to Latitude Zero, a beautiful colony beneath the ocean’s surface which is warmed by an artificial sun. The core conflict comes from Mackenzie’s rival, Dr. Malic, who wishes to destroy this utopia with his menagerie of genetically engineered monsters.

One of the most noteworthy parts of “Latitude’s” production is that it stars several American actors and was originally filmed in English. While there are patches where they were dubbed over, the Japanese cast members mostly speak in their own voices.

“Latitude Zero” is a marvel of world-building, due largely to the special effects and models employed throughout the film, many of which stand up to this day. The film works hard to make a fantastic setting feel real and for the most part it succeeds. Despite this, the story is undeniably campy. It can be hard not to laugh at the sight of Dr. Malic’s mutant bat men.

Extraterrestrial forces threaten the Earth in “School in the Crosshairs,” and only one girl has the power to stop them.

School in the Crosshairs

By contrast, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s “School in the Crosshairs” is determined to make its audience laugh. Teenager Yuka begins to develop powerful telekinetic abilities which are quickly called to action when a new student with similar powers aims to use them to win the student body election. With a story featuring magical aliens from outer space and avant-garde special effects, “School in the Crosshairs” asks if teenagers should fall in line or rebel against authoritarian structures.

Obayashi has expressed a radical distrust of dominant culture which can be felt throughout his filmography and in “School in the Crosshairs” in particular. Yuka is a star student at school, and when she begins to develop her powers, extraterrestrial forces reach out to recruit her to their world domination efforts. Hallmarks of young adult fiction are present here, such as heroic children and ignorant adults, and Obayashi’s unique acid trip-like special effects make a finished product that is marked by its absurd visuals.

Ruka is ready to paint the town red in her hunt for vengeance

Tokyo Gore Police

“School in the Crosshairs” is to post-modern what “Tokyo Gore Police” is to post-grindhouse. Just like in “School,” “Gore Police’s” protagonist Ruka is a young girl who must ultimately face off against an authoritarian power structure. Unlike in “School” this is largely accomplished through blood fountains, body horror, and mutilation.

A mad scientist named Key Man has developed a virus that mutates humans into bizarre monsters who sprout weapons from their injuries. These mutants, known as Engineers, are hunted down and exterminated by a special task force created by the now privatized Tokyo Police Force. Ruka is on her own journey of revenge as she searches for her father’s killer. The violence in this film is taken to such an excess that it puts David Cronenberg to shame, and it can be hard not to lose sight of the story’s politics next to the spectacle.

Described by his contemporaries as “the Tom Savini of Japan,” director Yoshihiro Nishimura has described the paintings of Salvador Dali as a major influence. Like Dali, Nishimura’s special effects aim to distort the human body into something alien and grotesque. While this essentially guarantees a lack of mainstream success, Nishimura has an intense cult following for his work and “Gore Police’s” anti-authoritarian slaughter is no exception.

Dreams and reality become indistinguishable from each other in “Paprika.”

Paprika

Visually speaking, “Paprika” strikes a balance between “School in the Crosshairs” and “Tokyo Gore Police.” It can be both surreal and grotesque, in several scenes at the same time.

Set in the near future, therapists have begun using a device called the DC Mini that allows them to enter their patient’s dreams. One of these therapists, Dr. Chiba, has begun using this device outside of company hours to help people and in doing so has developed an alter ego, the titular “Paprika.” The DC Mini gives the user unrestricted access to people’s subconscious—a power whose danger is realized when one of them is stolen and used to make the scientists responsible for the project attempt to kill themselves.

The line between real life and dreams blurs and eventually disappears entirely in Satoshi Kon’s visual marvel. “Paprika” is oftentimes unsettling, and both the protagonists and antagonists break the rules in their quest to accomplish their goals, and the film shows how easily the world that makes sense can be pulled apart by our subconscious. While it should not be approached unprepared, “Paprika” is a stunning film.

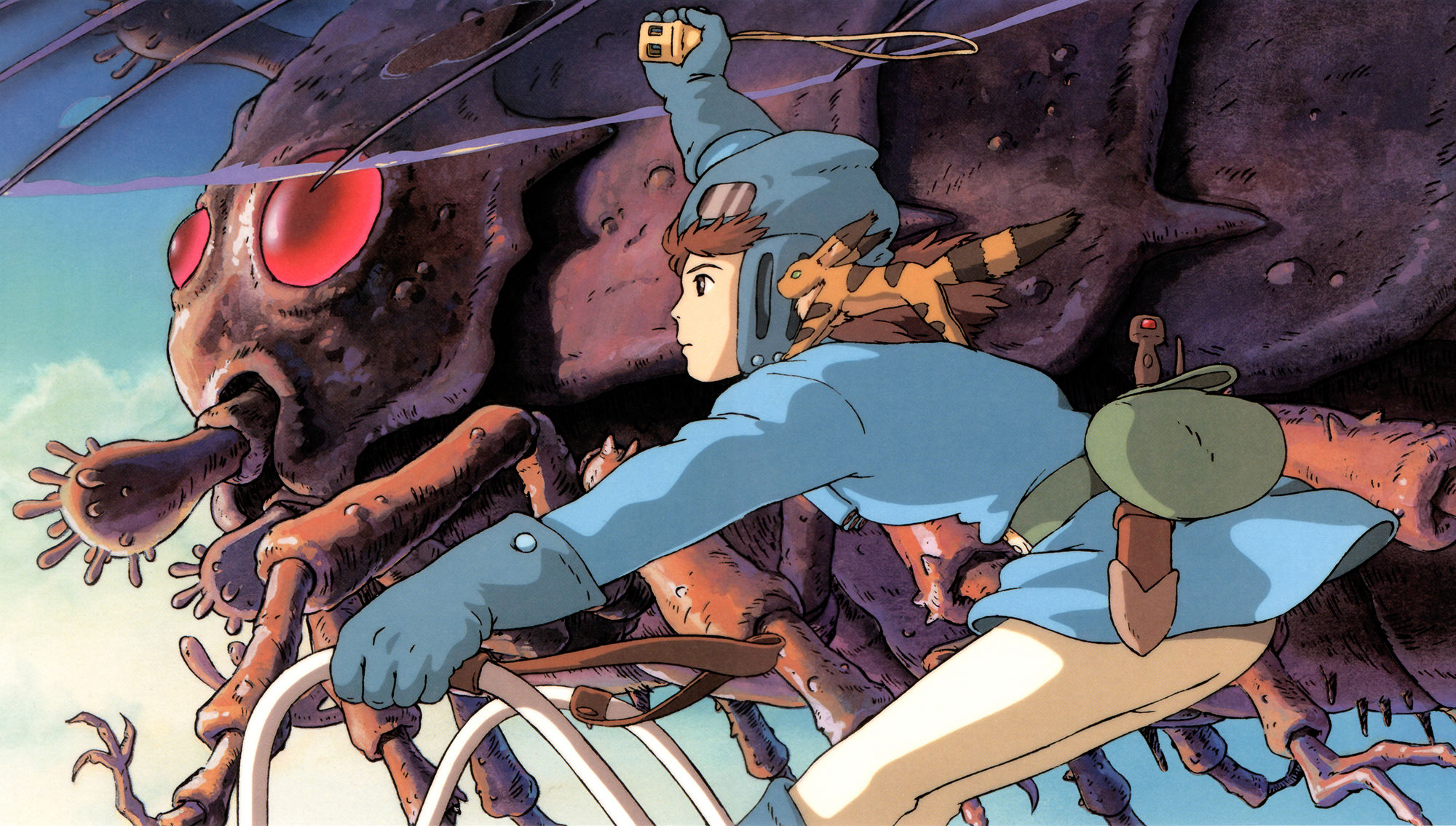

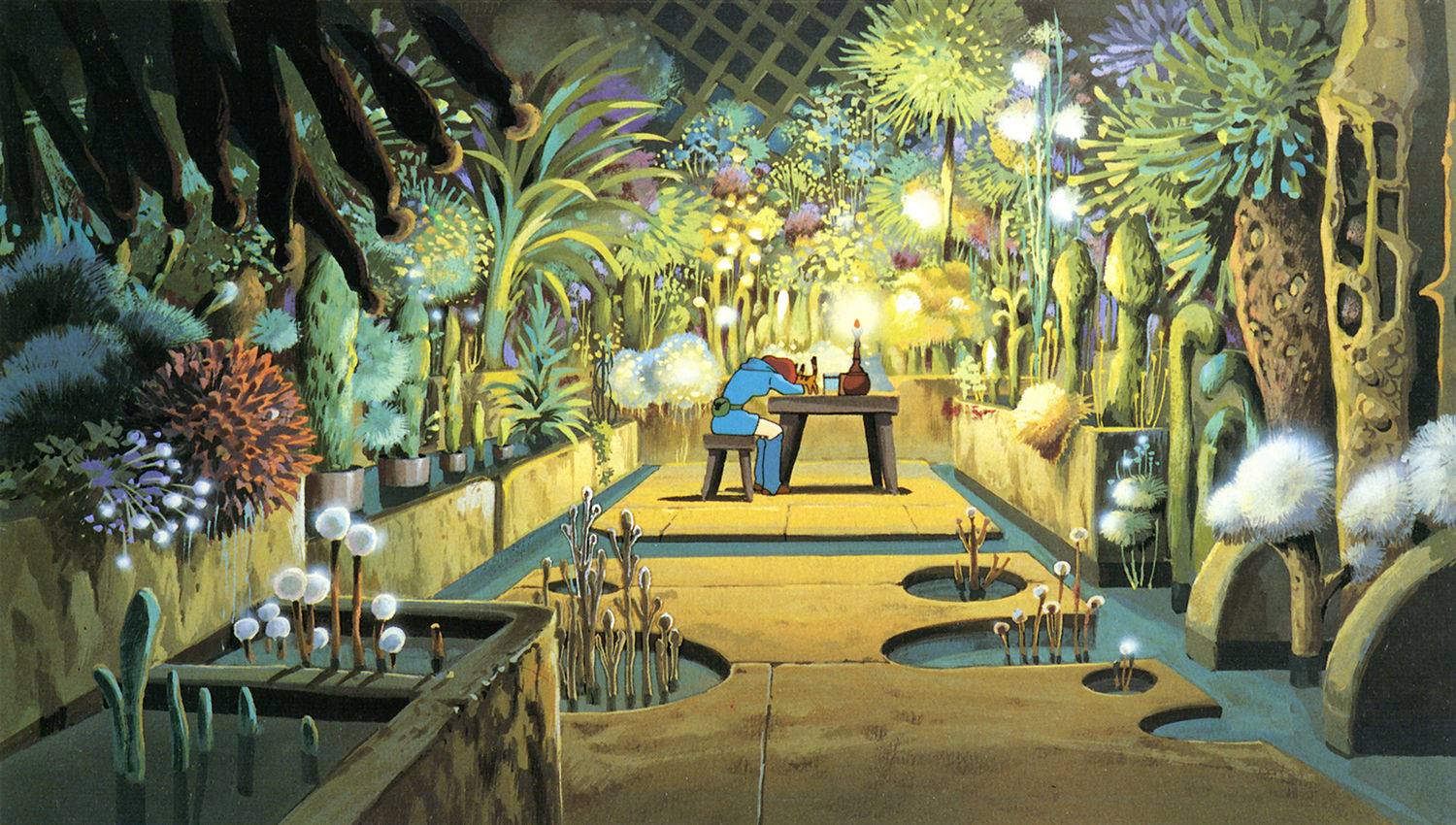

Miyazaki’s penchant for breathtaking visuals is in full effect here.

Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind

It would be a crime to discuss Japanese science fiction or fantasy without mentioning the work of Hayao Miyazaki. “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind,” while being one of his earlier projects, still bears the spectacle and level of quality that made Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli internationally renowned.

The film is set in a world after the end of the world in which complicated technology exists, but humans are forced to scavenge and live in isolated communities, some of which live alongside the natural world and others that seek to conquer it. The titular Nausicaa is an explorer who seeks to learn about and understand nature. She frequently leaves her wind turbine-powered village to explore the poisonous and giant bug-filled jungle a short distance away.

When the militant Tolmekians bring their airships and soldiers to Nausicaa’s home, she is set on a collision course between two warring nations and the giant insects who threaten to destroy the humans who remain. The story has strong environmentalist themes, and makes it clear that no matter what destruction humanity brings we will ultimately only bring it on ourselves. The natural world will survive and come back, even if it takes thousands of years. It’s up to humans to learn to live sustainably alongside the forces of nature, which is a theme that is not unfamiliar to other films on this list.

“Steins;Gate” is a rare example of a time travel story done well.

Steins;Gate

While “Nausicaa” deals with a post-apocalyptic world, “Steins;Gate” presents a puzzle to avoid that world entirely. Or at least the original series did. Released as a visual novel in 2009, the story was adapted to a manga later that year and then into an anime in 2011. “Steins;Gate: The Movie—Load Region of Déjà vu” is set one year after the events of the anime and ties up the loose ends that the initial story left.

Where the series focused on self-proclaimed mad scientist Rintaro sending text messages and memories into the past to alter the present and save the life of neuroscientist Kurisu, the film instead focuses on Kurisu as she tries to save Rintaro from the consequences of his mucking about with different timelines. The series is overshadowed by the threat of malevolent forces acquiring this fantastic technology and using it to ignite World War III, but the film is instead a love story. Kurisu is forced to choose between her loyalty to Rintaro and the possibility that she could suffer the same fate that he does.

This film, while possessed of generally positive critical feedback, has a wealth of required research in order to really enjoy. Since it is a direct continuation of the events of the anime, interested parties should prepare for a 24 episode marathon before viewing it.

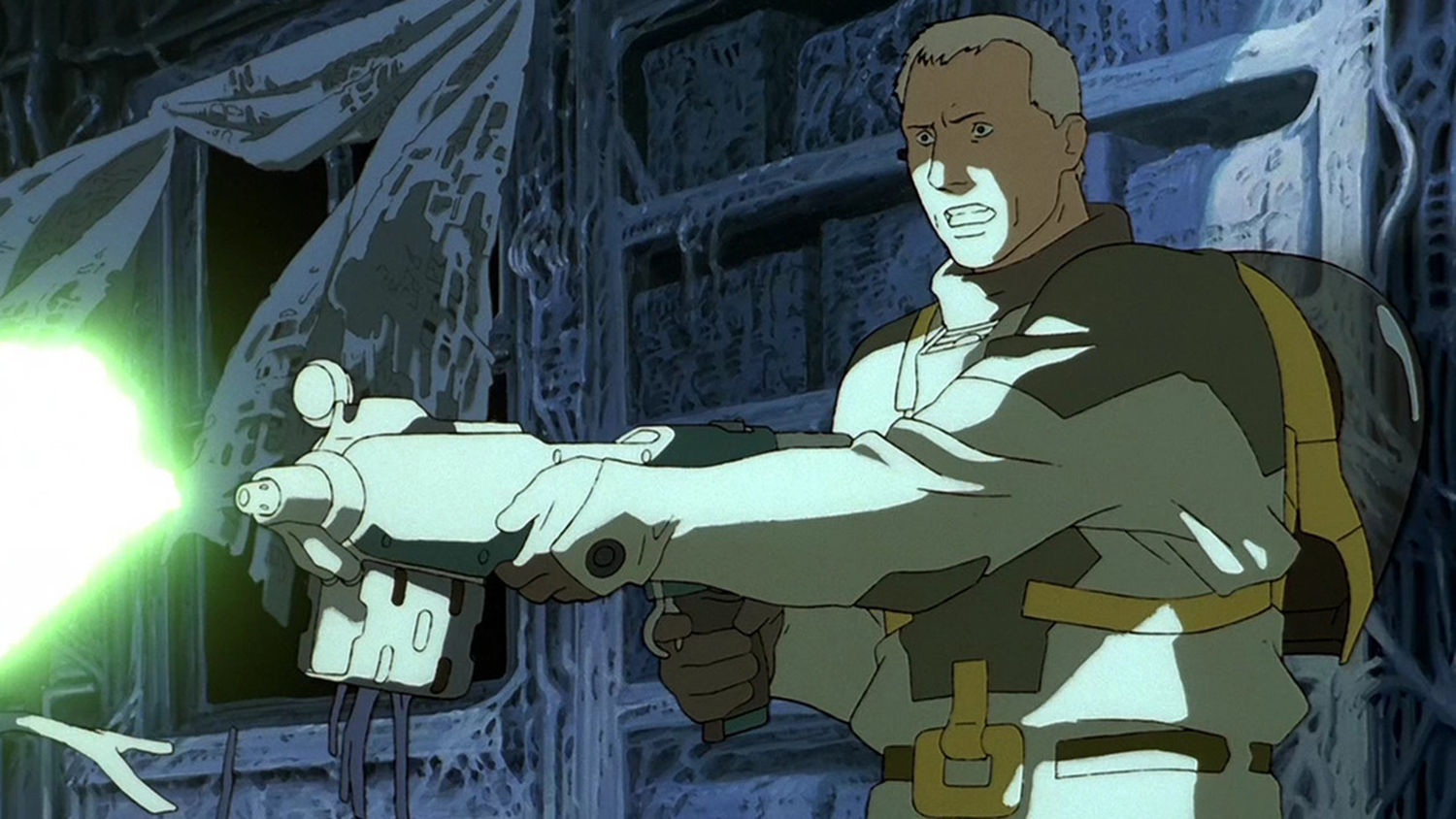

“Otomo’s Memories” aims to unsettle.

Memories

“Memories,” by contrast, is not just one self-contained story; it is three. Also known as “Katsuhiro Otomo’s Memories,” the film’s three narratives are adapted from Otomo’s manga short stories. Otomo is best known as the creator of the manga “Akira,” and his work frequently bears themes of isolation and government corruption. “Memories” is no exception.

The first story is titled “Magnetic Rose.” It is a space-age ghost story set on an abandoned deep space freighter. The second, “Stink Bomb,” has an unsuspecting scientist become the walking source of a biological plague that threatens all of Tokyo. It was loosely inspired by the Gloria Ramirez incident in California. The third and final story, “Cannon Fodder,” is set in a walled city where most of the buildings also act as artillery against an enemy that average citizens have no way of seeing. Their lives revolve around maintaining or firing these cannons, and they must rely on the news media to know if they are even hitting their targets.

Reminiscent of “Tales from the Crypt” and “Heavy Metal,” these richly atmospheric stories are mainly plot-driven spectacles to unsettle and disturb.

Photos © respective film studios