Salvador Dali didn’t suffer from phobias, he reveled in them. His list of pathological fears ran from childhood ereuthophobia, a fear of blushing, to acrididophobia, a fear of grasshoppers. A general fear of insects was connected to delusional parasitosis—a feeling of nonexistent bugs infesting one’s skin. He also feared, among many other things, the female body and becoming a father.

These powerful phobias were matched by profound fascinations. Dali was obsessed with eroticism and masturbation, and with dreams; his visual vocabulary included heads, eggs, elephants, crustaceans, and butterflies, all with psychological, mainly Freudian, reasons for appearing on canvas.

Dali’s surrealistic images retain their impact decades later, and they’re always worth another look.

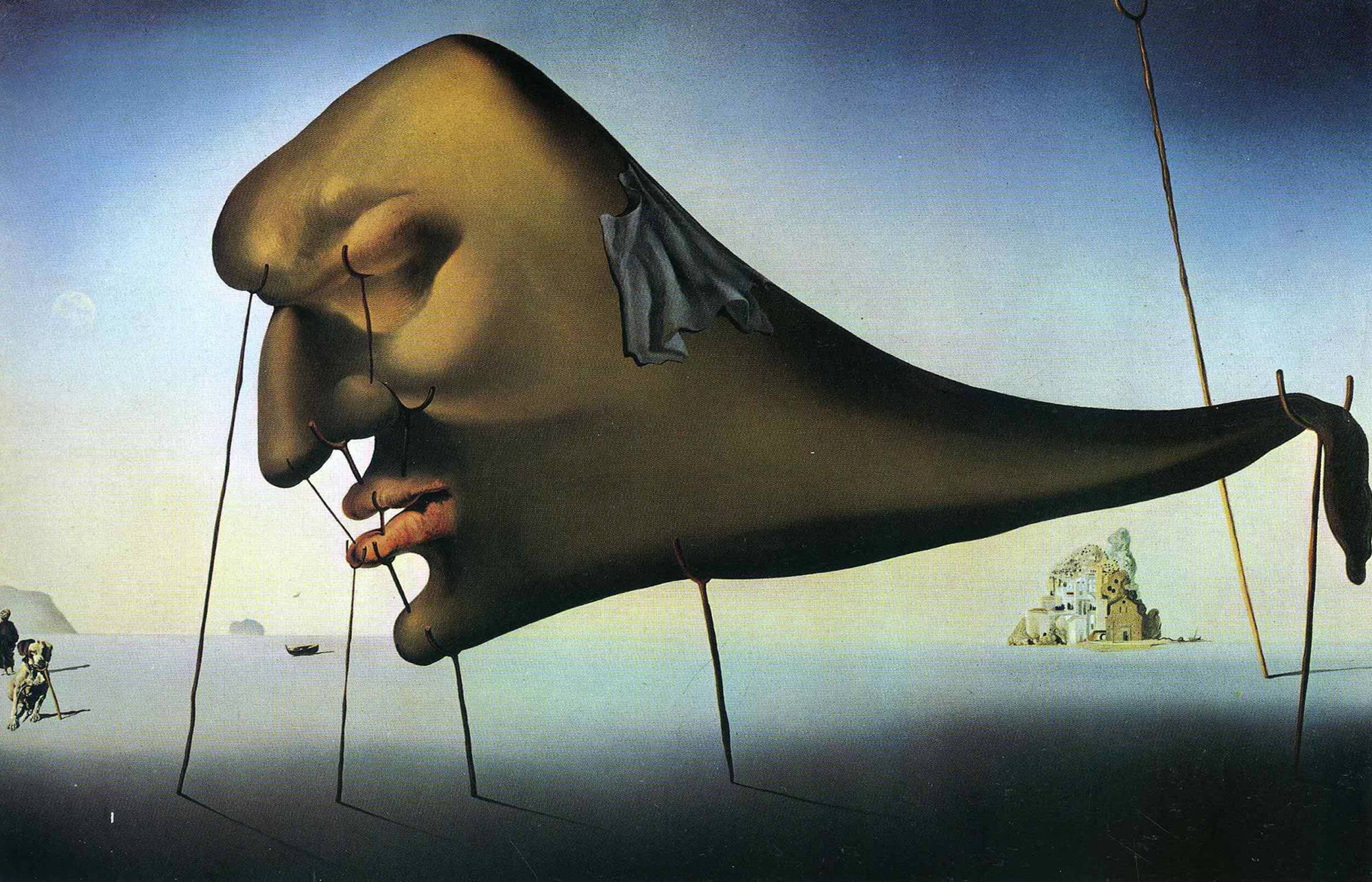

Top: “Sleep”(1937) by Salvador Dali, suggests the realm of dreams, where his imagination dwelled.

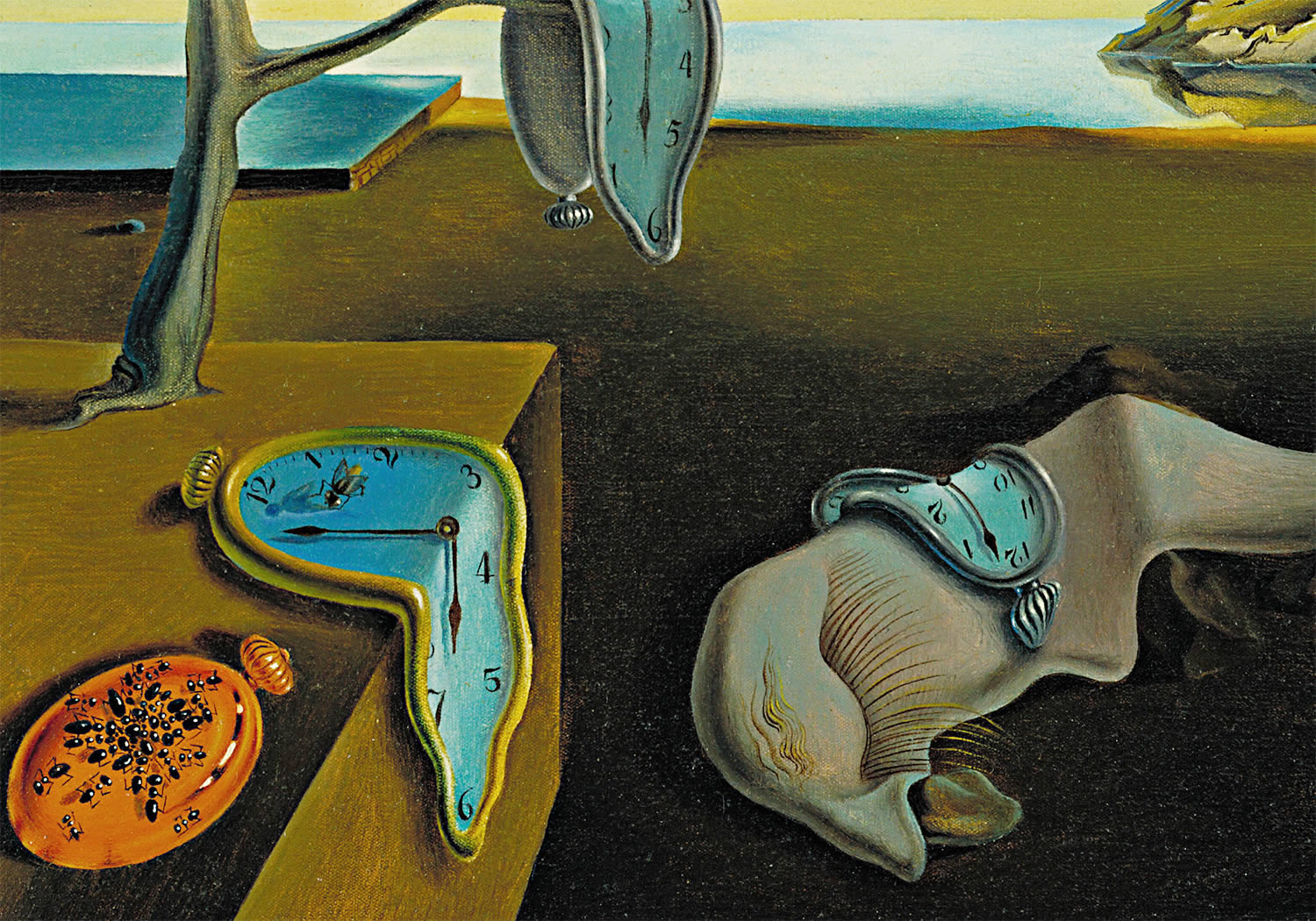

Ants mark the inevitable passing of time in “The Persistence of Memory” (1931).

Insects

Crawling and swarming black ants. Beautiful, colorful butterflies floating individually and in clusters. An oversized lone grasshopper perched over the mouth of a deformed head. Dali’s paintings are infested with the very insects that terrify him. Ants, a common image, signify decay, suggesting also a fear of death. Grasshoppers, which pop up with some regularity, he so feared as a child that other children threw them at him for fun, just to see him react. [1]

Can “The Persistence of Memory” really be that small? Astoundingly, yes. Photo © Christina Whiting.

Tiny Things

Dali was endlessly fascinated with all things small. Not just insects, but things like olives, breadcrumbs, grains of sand, and later blackheads and arm hairs also drew his focused attention. He believed that little things had the power to disrupt beings a hundred times bigger than themselves. [2] And many of his early paintings are surprisingly small. The iconic “The Persistence of Memory” may loom large in the history of modern art, but it measures a mere 9 ½ by 13 inches, barely larger than a piece of printer paper.

Here a lobster, there a lobster, everywhere a lobster.

Crustaceans

In Dali’s symbolic vocabulary, an exoskeleton represented armor protecting the soft creature within. It was a concept he thoroughly related to, being himself a vulnerable hermit crab in need of a hard shell to protect him from the outside world. [3] Lobsters especially had a starring role, not only in paintings, but also printed on a dress for the designer Elsa Schiaparelli and fabricated in plaster and affixed to the handset of a 1930s rotary phone.

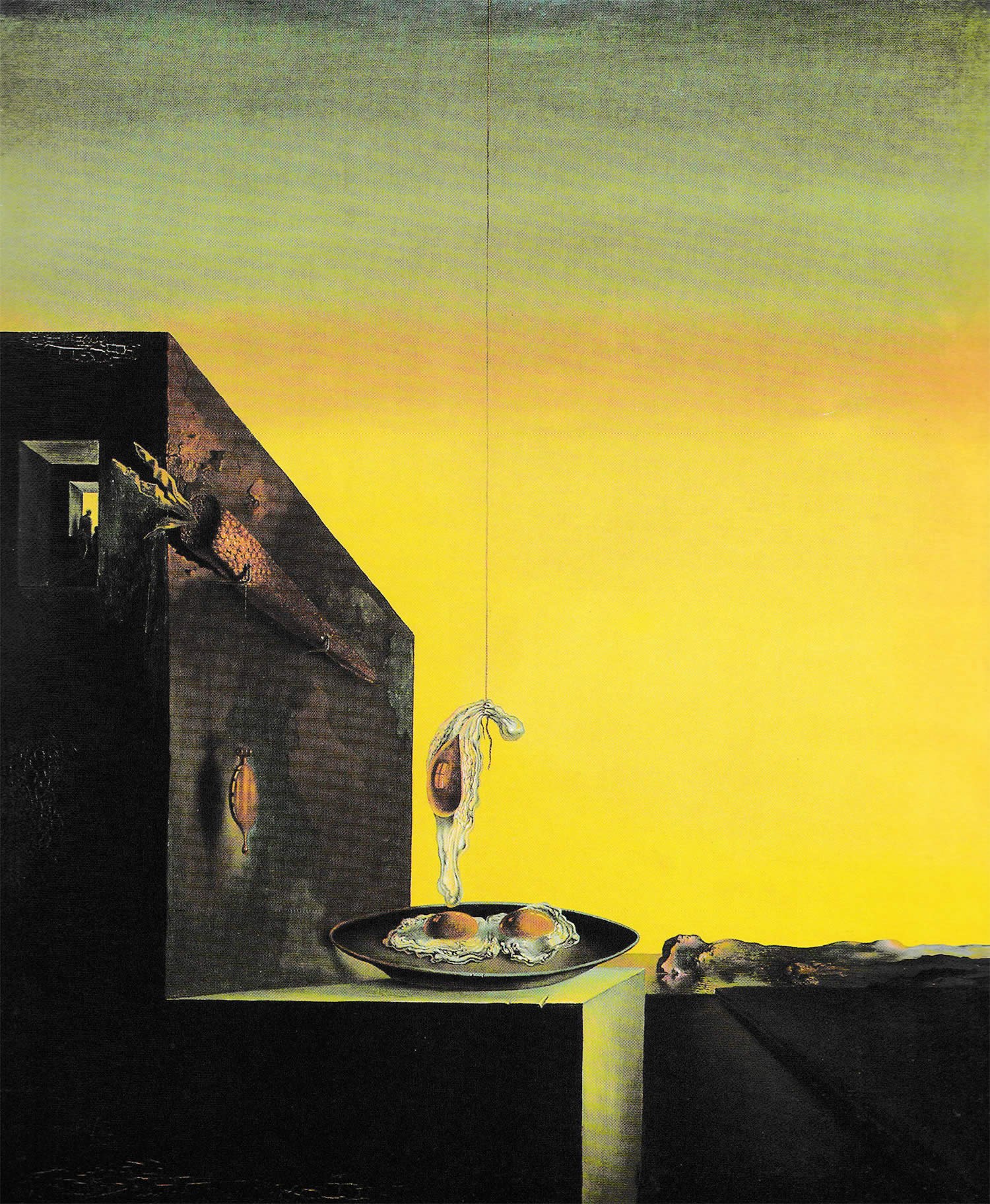

“Eggs on the Plate without the Plate” (1932). Hard on the outside, soft and squishy inside.

Eggs

Like a crustacean, an egg has a hard shell protecting a soft interior. Eggs are fundamentally prenatal and intrauterine, so they also symbolize birth, new life, and hope, and Dali had a distinct fondness for them. They appear whole, as in “Metamorphosis of Narcissus,” or cracked open and cooked, as in “Eggs on the Plate without the Plate” (shown above). Dali’s home in Barcelona has egg sculptures nestled in alcoves, and at the Dali Museum, giant eggs crown the top of the building.

Beware of lions—and genitals—with sharp teeth! “The Accommodations of Desire” (1929).

Female Sexuality

Ironically, given his love of eggs, Dali was terrified of their origin. Female sexuality and its component parts terrified the artist, as graphically evident in “The Bleeding Roses,” with its literally visceral imagery of a woman’s dripping abdominal organs. In “The Accommodations of Desire” (above), lion’s heads are meant to signify vagina dentata. The toothed vagina, a powerful image from folklore, represents a woman’s potential to injure or even castrate a man during intercourse, the root of Dali’s phobia.

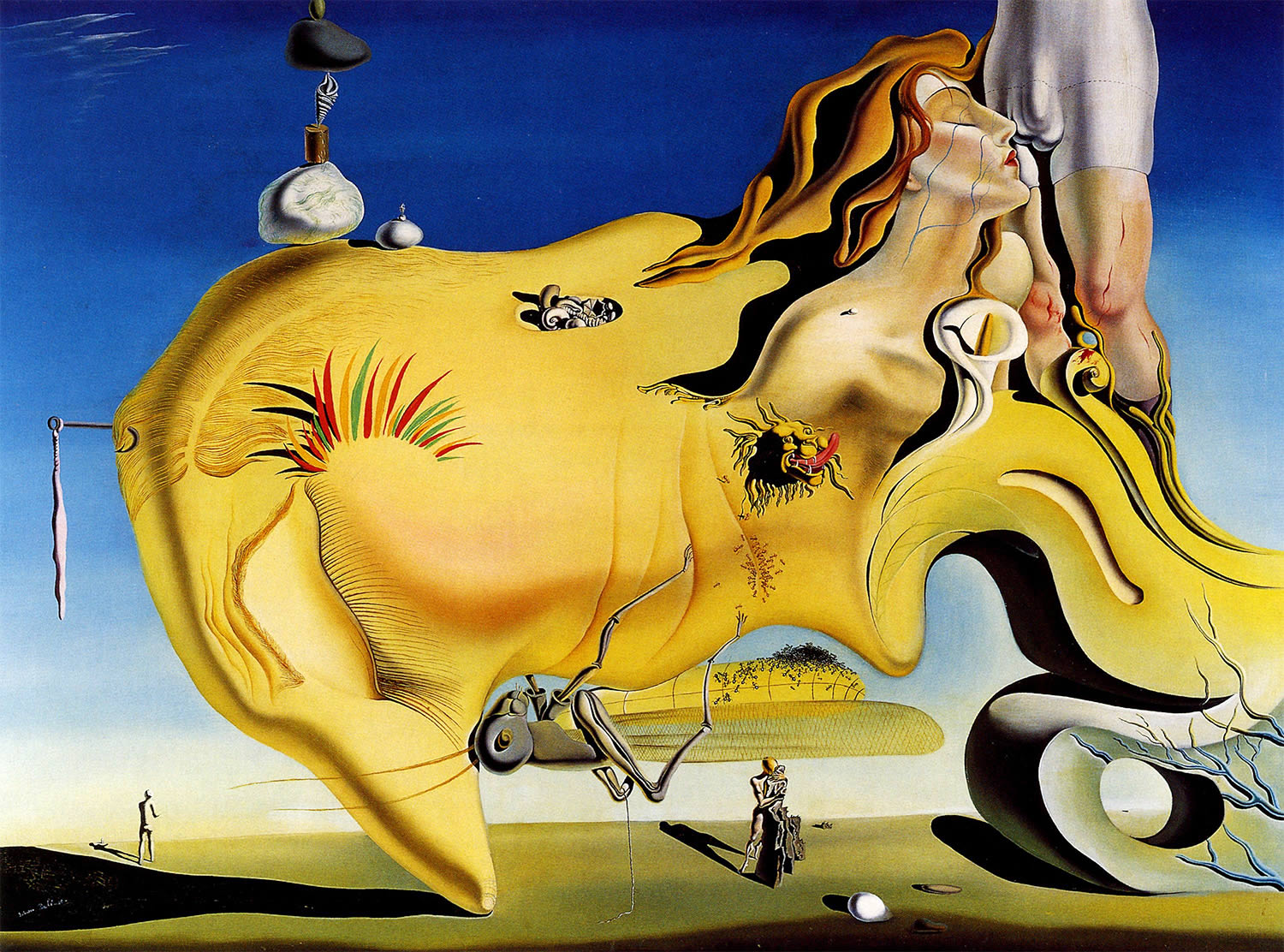

“The Great Masturbator” (1929) assaults the viewer with many of Dali’s frequently used symbolic images.

Masturbation

Dali had an aversion to sex, but he was obsessed with masturbation, and it’s been suggested that it was almost his only form of sexual activity. References in his paintings are obvious in “The Great Masturbator” (i.e., Dali himself, though the image doesn’t depict the act), and “Hitler Masturbating,” a watercolor done late in the artist’s career that comes off as a dirty joke. In “Le Jeu Lagubre,” what gives it away is the emphasis on a man’s hands, one covering his face and one, oversized, reaching out. [4]

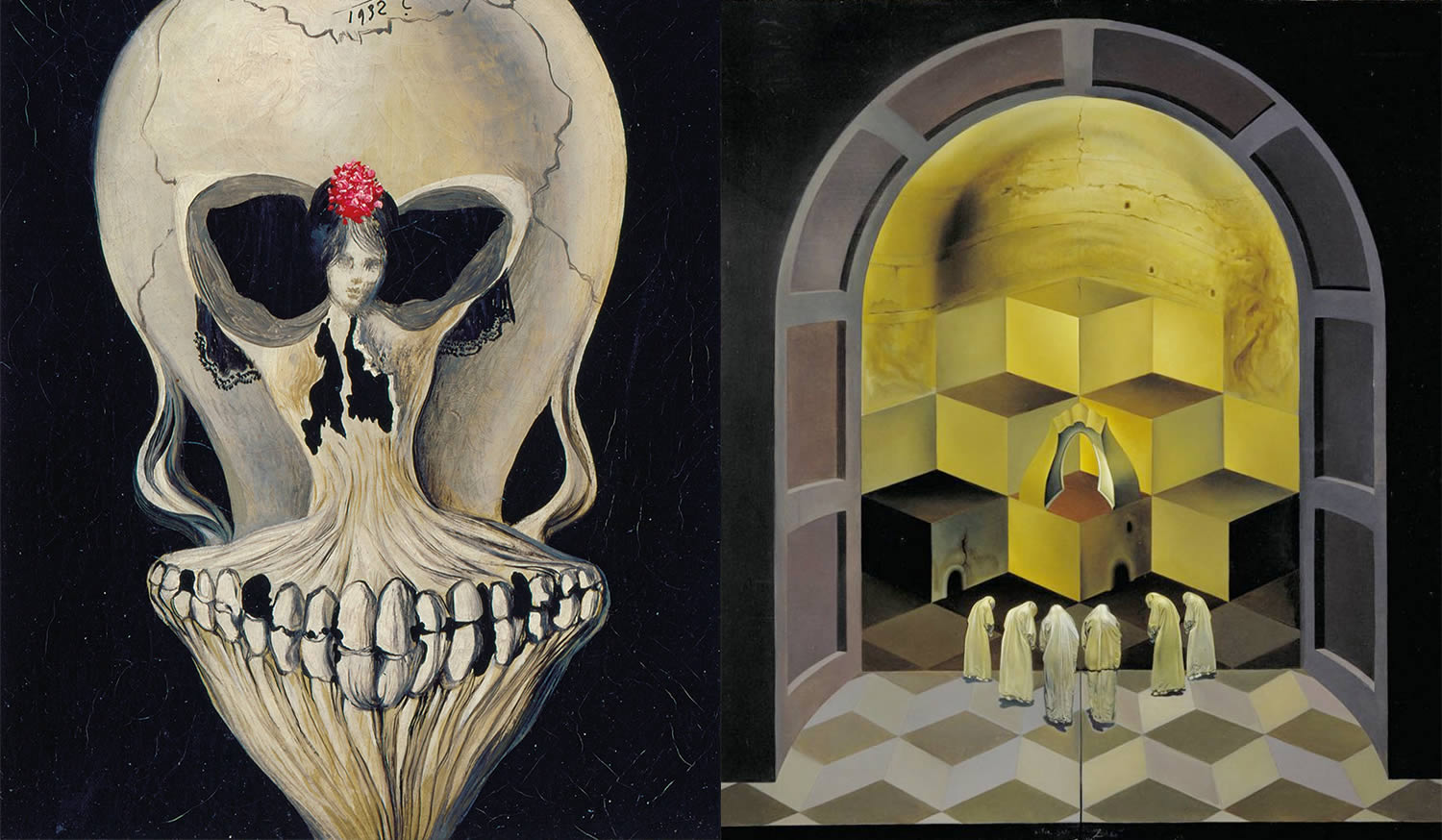

The skulls in “Ballerina in a Death’s Head” (1939) and “Skull of Zurbaran” (1956) are not-so-subtly hinted at.

Skulls

True to his paradoxical nature, Dali was both frightened and compelled by death. Skulls, a clear representation of human mortality, appear regularly in his paintings. In “Atmospheric Skull Sodomizing a Grand Piano,” the skull is warped and disturbing. In “The Face of War,” iterations of skulls reside within the orifices of a horror-stricken head. Most famously, he would depict a skull indirectly by using other elements of the image, as in “Ballerina in a Death’s Head“—a technique that has inspired countless artists since.

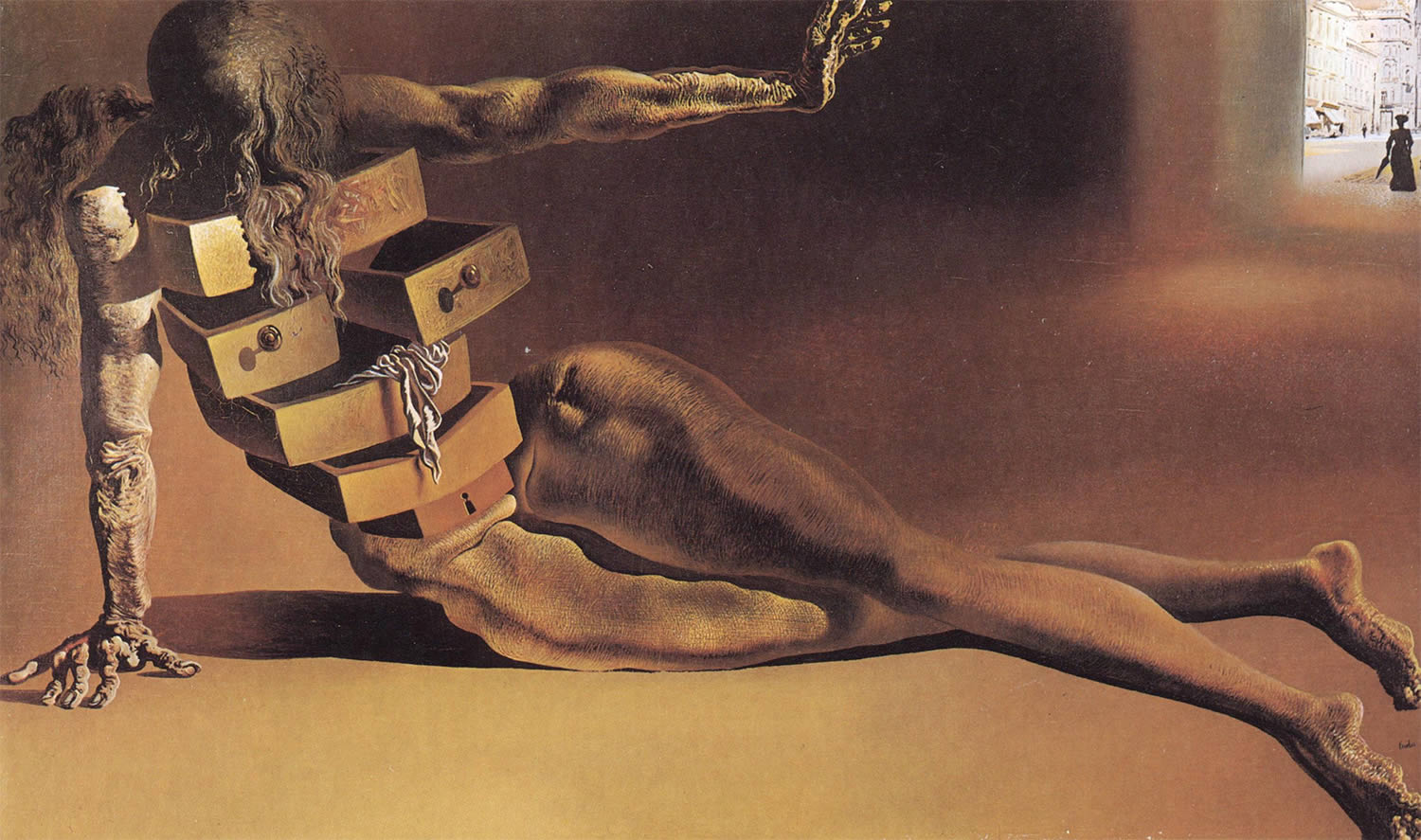

A faceless old man reveals his inner self in “The Anthropomorphic Cabinet” (1936).

Drawers

The writing of Sigmund Freud, especially The Interpretation of Dreams, enthralled Dali, and in fact the two met shortly before the psychoanalyst’s death. What resonated with Dali was Freud’s approach to the hidden recesses of the mind—the subconscious, the source of dreams and the driving force behind the artist’s work. The paintings “The Anthropomorphic Cabinet” and “The Burning Giraffe” exemplify Dali’s use of drawers integrated into the human form to signify these hidden aspects of the self.

Well established as an artist, Dali turned to religious themes in the late 1940s. Photo © Getty Images.

Religion

Conflicted from childhood by his mother’s Catholic faith and his father’s aversion to religion, later in his life Dali experienced a renewal of faith and embraced the iconography of traditional Christianity. He became fascinated with its metaphysical aspects and the possibility of integrating religion and science. Starting in the late 1940s and into the ’50s, he created a series of overtly religious paintings depicting the Last Supper, several versions of the crucified Christ, and the Madonna as portrayed by his longtime muse and companion, Gala.

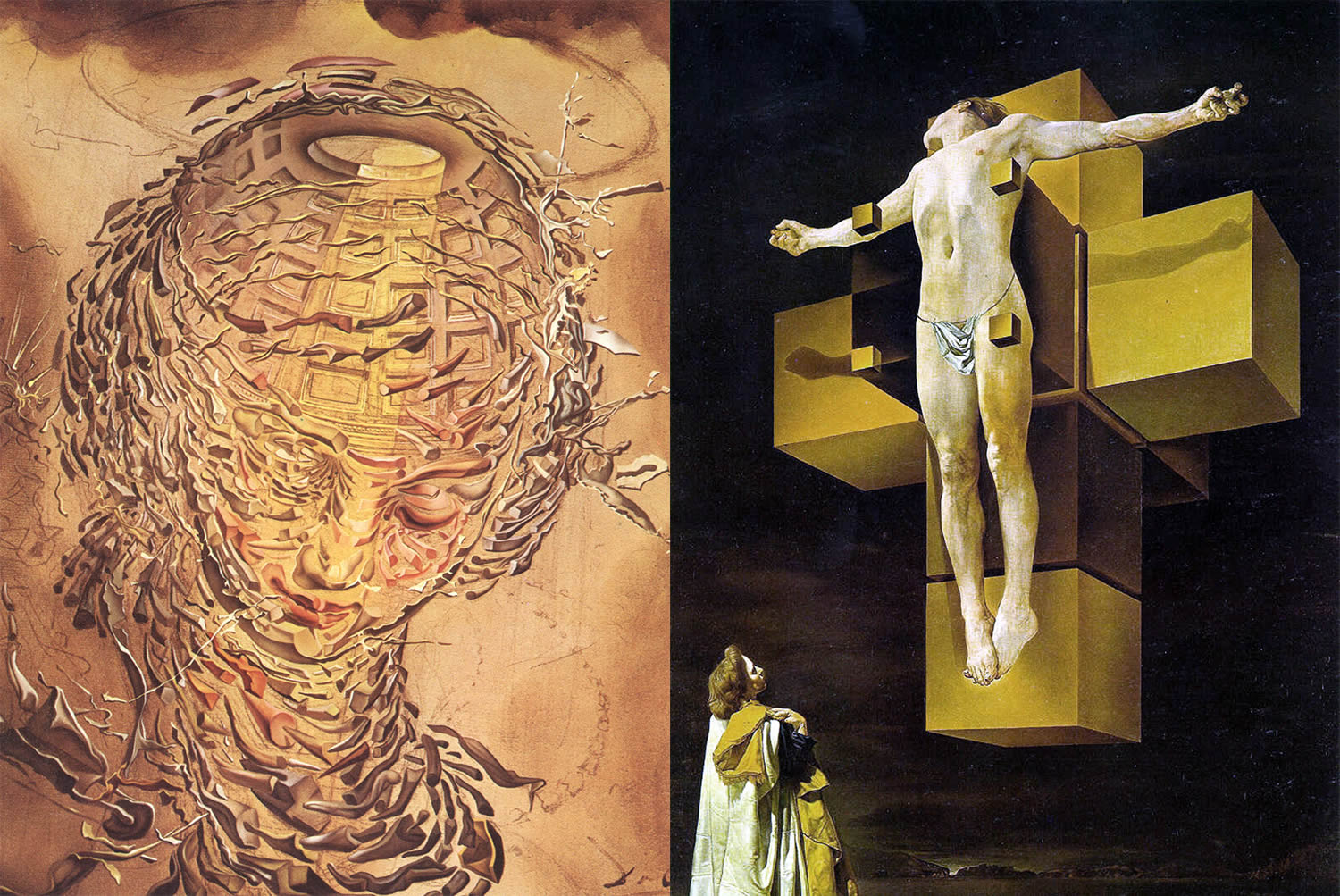

The atomic bomb provided inspiration for “Exploding Raphaelesque Head” (1951).

Science/Physics

In conjunction with a renewed religious fervor, Dali developed an intense fascination with science, particularly quantum and nuclear physics. He devoured issues of Scientific American and loved to discuss its contents. [5] It was the atomic age, the advent of nuclear weapons, and he worked the science into paintings like “Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus)” with its metaphysical, fourth-dimensional crucifix, and “Exploding Raphaelesque Head,” an homage to Raphael’s Madonna, shattered into atomic fragments.

Bibliography: 1. Meisler, Stanley “The Surreal World of Salvador Dali,” Smithsonian, April 2005. 2. Rothman, Roger, Tiny Surrealism: Salvador Dali and the Aesthetics of the Small, University of Nebraska Press, 2012. Accessed on Google Books. 3/4/5. Etherington-Smith, Meredith, The Persistence of Memory: A Biography of Dali, Random House, 1992.

Images © Gala – Salvador Dali Foundation.