Note: Contains sexual references and nudity.

True artists are distinguished by the complex emotions they bring to the artistic process and by the enduring impact of their art.

In the 1970s Robert Mapplethorpe, in his 20s, conceived of a successful career as a photographer. From the start, his work stunned the art world. More than 25 years since his death, his influence on photography—and on the question of what constitutes art—continues to ripple through the culture. Mapplethorpe exhibits are a perennial staple at progressive art museums.

In many people’s minds, Mapplethorpe is synonymous with obscenity. There’s no denying many of his images are obscene, but it’s not done for obscenity’s sake alone. With a precise sense of vision and the passionate soul of an artist, Mapplethorpe confronts us with bold images, many of them taken in an underground world of bondage and danger. These pictures pushed a lot of buttons when they first appeared, and they keep pushing buttons decades later. These days, thanks to the Internet, BDSM has come out of the shadows and we see it everywhere—but Mapplethorpe’s pictures still have the power to shock us. Here’s a look at 5 major aspects of the artist’s life and work.

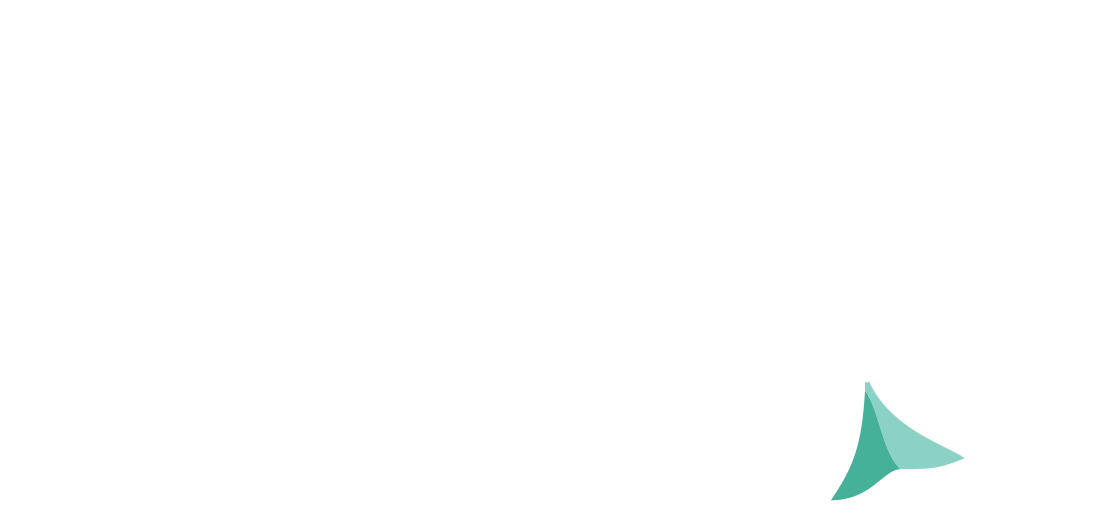

Above: In a self-portrait from 1980, the artist shows he’s in touch with his feminine side. Photo © The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.

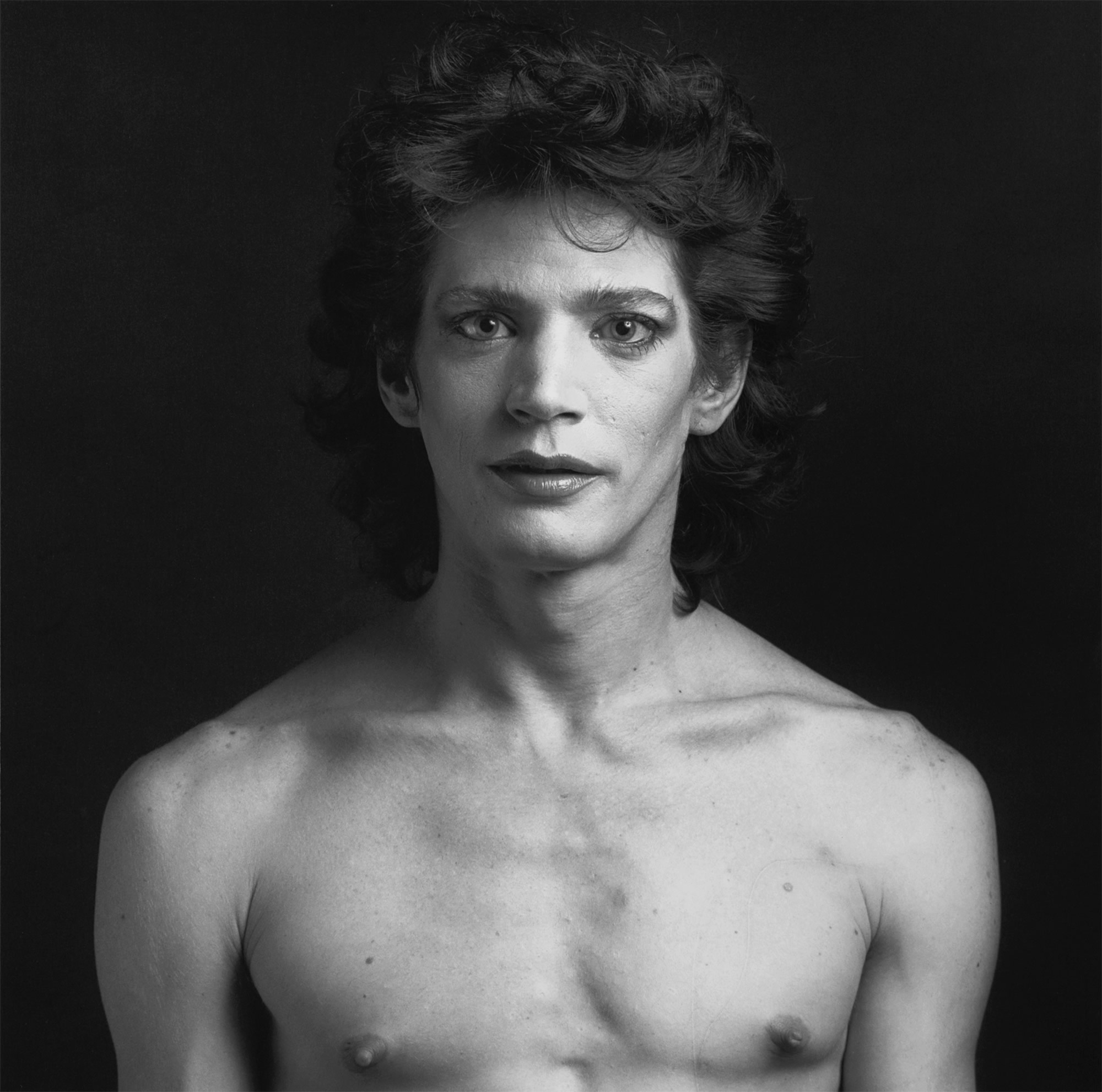

Top: Men loving men was not a common sight when Mapplethorpe posed this couple for “Two Men Dancing” (1984). Middle: Shades of sadism come out in a self-portrait from 1983. Bottom: “Man in Polyester Suit” (1980) cemented the artist’s reputation, and in 2015 sold for nearly half a million dollars.

Homosexuality

Coming of age sexually in 1970s New York City, Mapplethorpe was on the cusp of shifting trends in homosexuality. Pushing back against the stereotype of effeminate gayness, “activists advanced the notion that a man could be both gay and virile.” For many gay men, this was played out in the S&M subculture, where they “enacted complicated master-slave scenarios that tested one’s masculinity.” For Mapplethorpe, being gay and testing one’s sexual limits went hand-in-hand. He took his camera, and his desires, into the deepest, darkest recesses of sex play.

Tragically, Mapplethorpe, like so many of his contemporaries, would be among the early victims of AIDS, which also went hand-in-hand with being gay at the time. But before he died, at 42, he ensured the solidity of his legacy by creating a foundation, based on the phenomenal high-ticket sales of his photographs. The Mapplethorpe Foundation provides funding for AIDS research and treatment at major institutions in New York and Boston, and for the continuing advancement of photography as an art form.

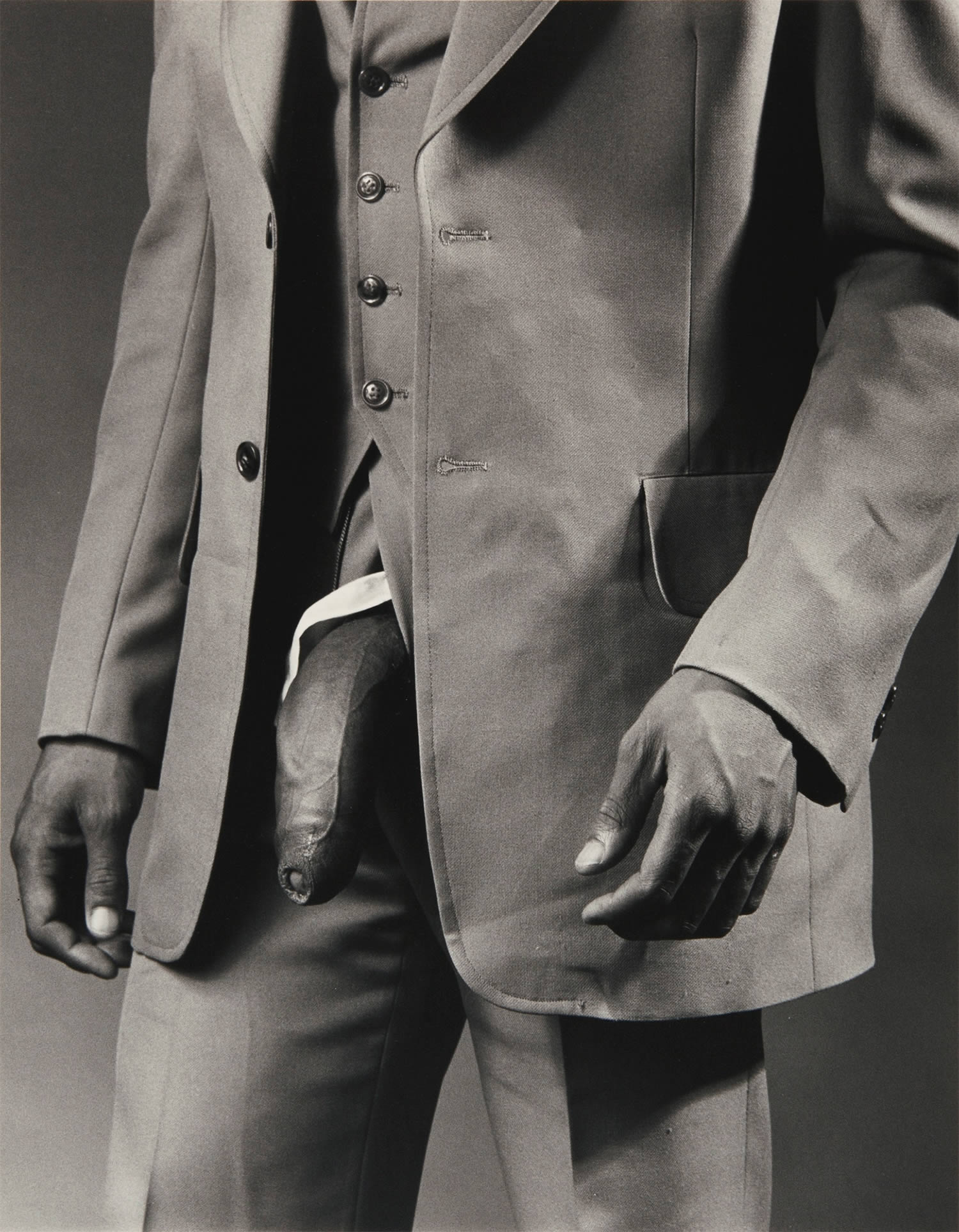

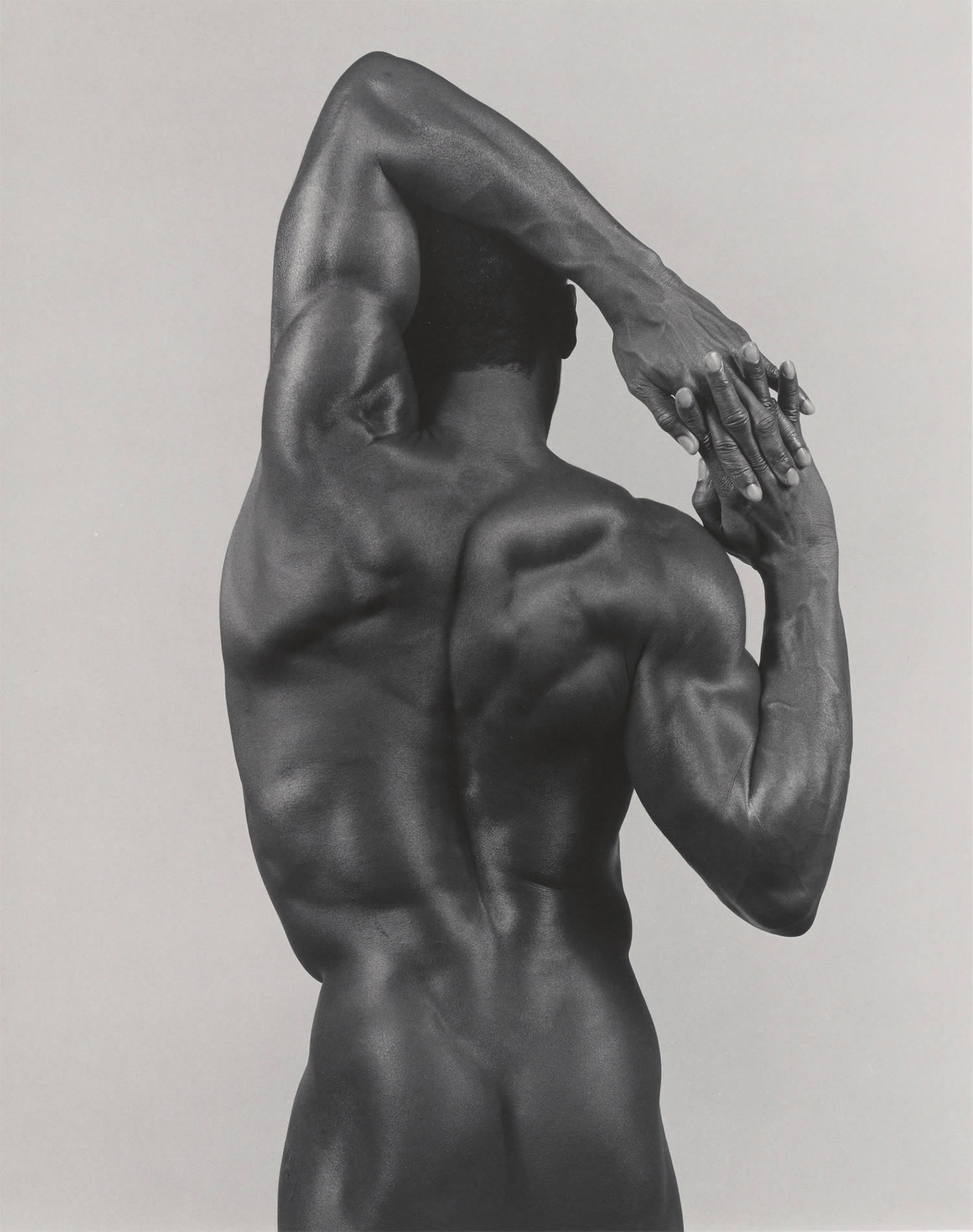

Mapplethorpe was relentless in his pursuit of black men. Above: “Ken Moody and Robert Sherman” (1984) and “Derrick Cross” (1983).

Racism

Immersed in the steamy underbelly of the city’s gay scene, Mapplethorpe became obsessed with black men. Cross-racial sex was still radical—very exotic and highly alluring to white men. To men like Mapplethorpe, black men were built better, bigger, more beautiful—every stereotype come to life. It was an aesthetic perspective, but it was also racist. Mapplethorpe threw around the n-word with blatant disregard, and he made no secret about seeking a black man who was “free enough” to let him use the offensive word in bed.

The photos he took of black men are among the strongest in his vast body of work. As seen through Mapplethorpe’s lens, the black male body is a finely wrought sculpture, a carving of darkest ebony, a solid platonic form occupying space in the most assertive way possible.

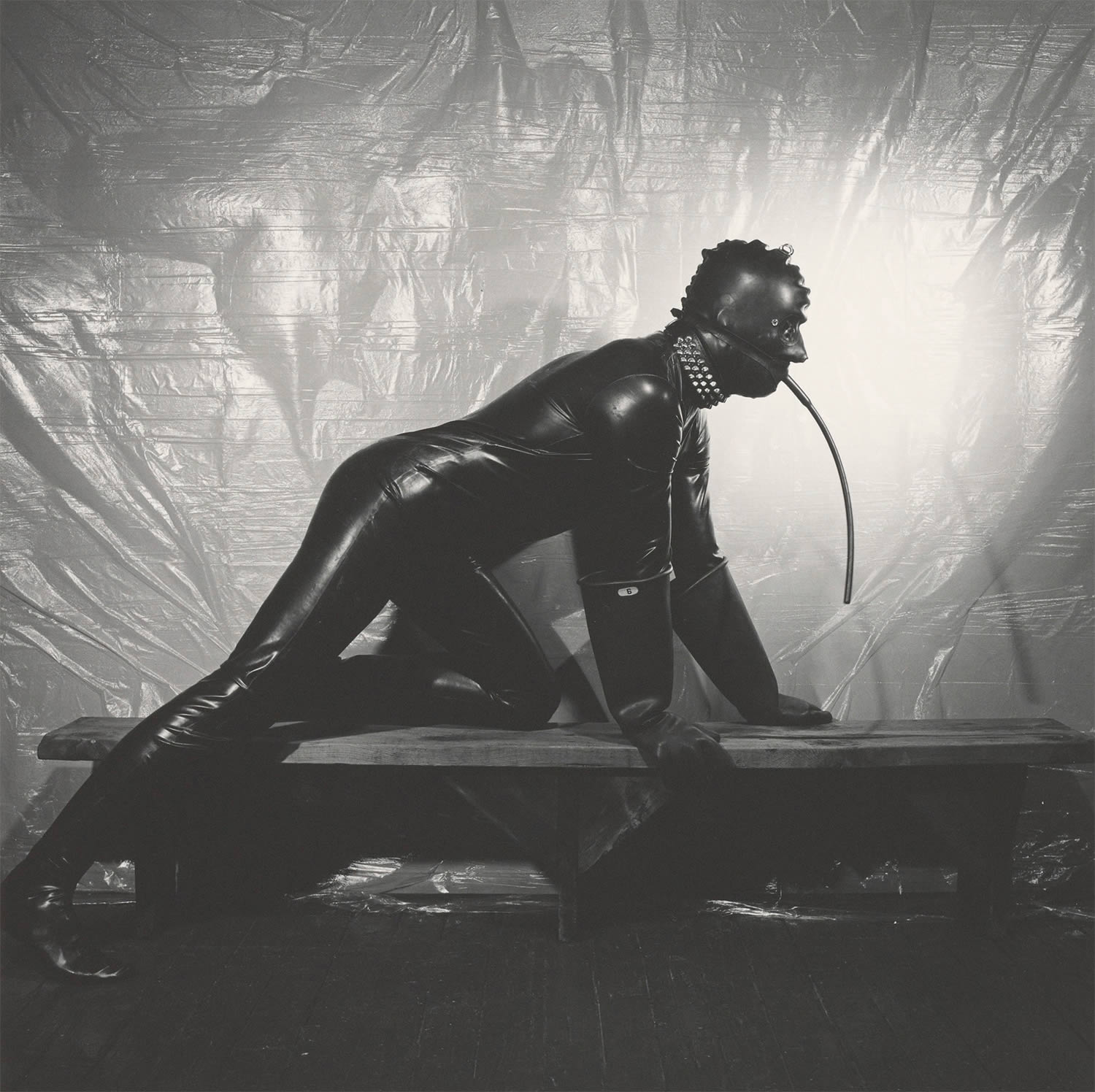

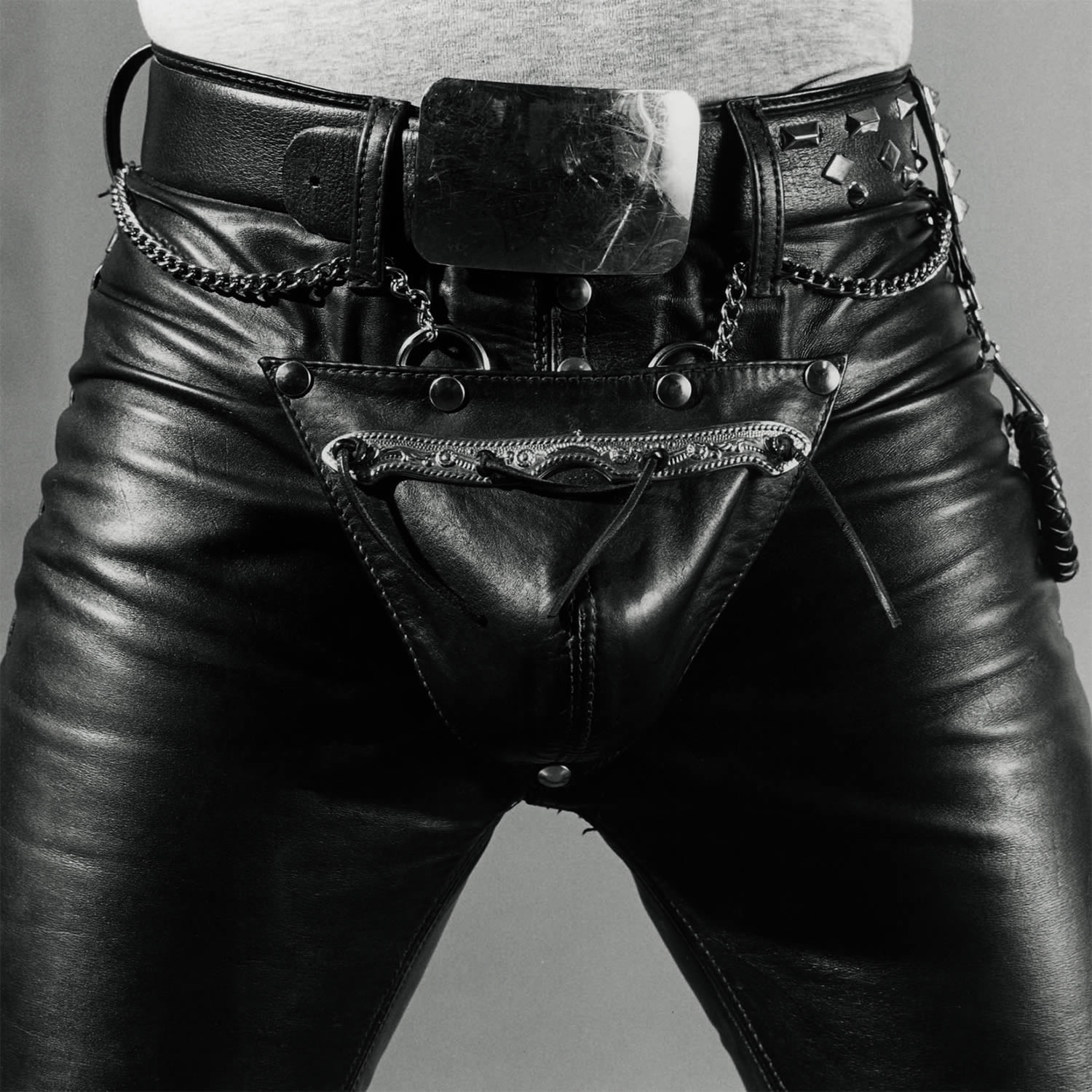

Photos like these opened the door to a dark underground world of bondage and domination, sadism and masochism, where gay men tested their personal limits.

BDSM

Raised in a Catholic family, Mapplethorpe was well acquainted with concepts like sin and guilt and punishment. Add in his innately dark sensibility and adventurous spirit, and no wonder he was drawn to the BDSM world like a moth to flame. What was different was his definition of S&M: for him it was not sadism and masochism, it was sex and magic. “Sex is magic,” he said. “If you channel it right, there’s more energy in sex than there is in art.”

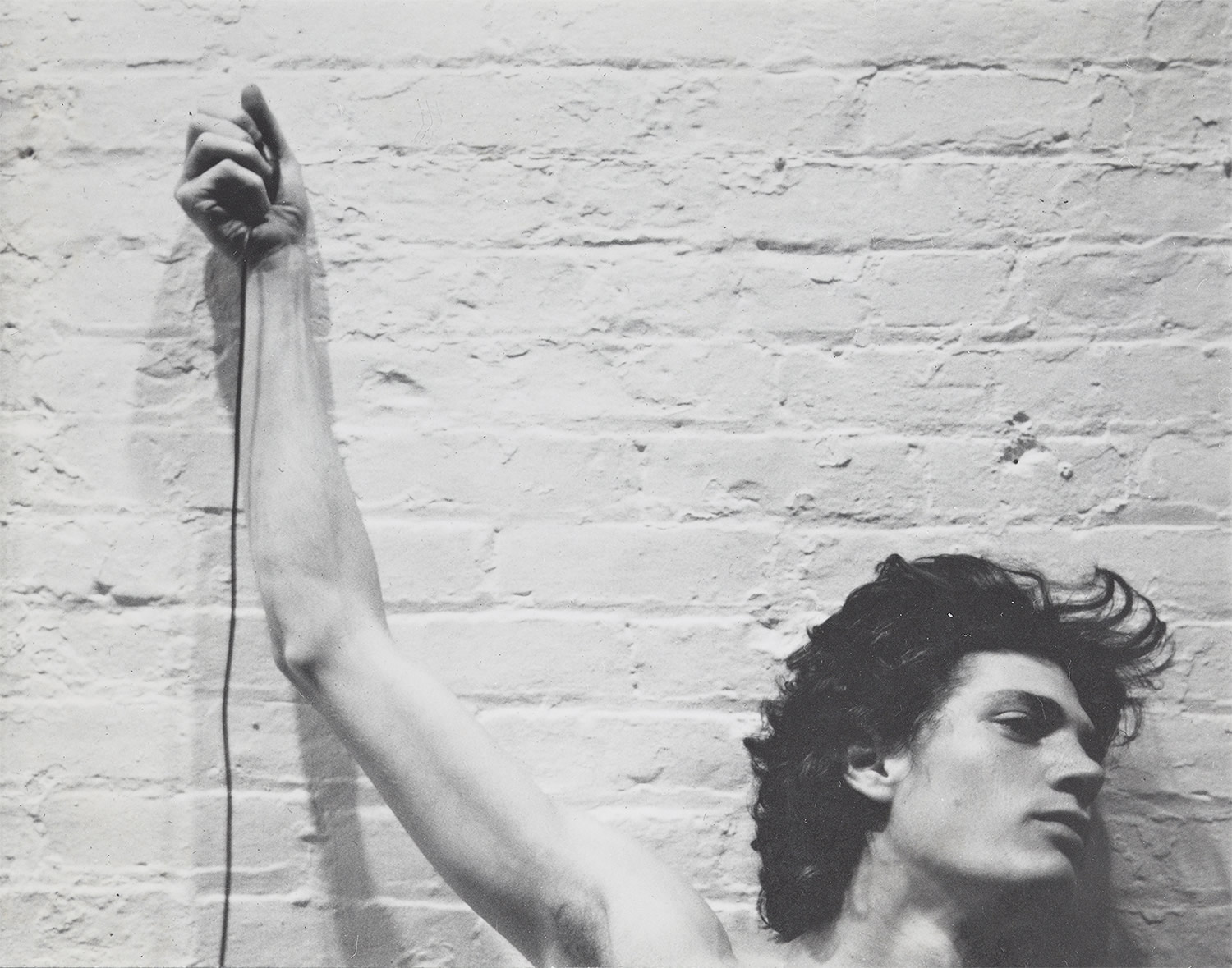

What was different about his work in BDSM was his turning the tables on the more commonly seen imagery of so-called deviant sex, a hetero fantasy of submissive women bound in ropes against a posh backdrop. Mapplethorpe showed submissive men without any context at all, often decontextualizing them further by cutting off body parts at the edge of the frame. He exposed the world to outlandish sexual acts and instigated heated controversy that smolders to this day.

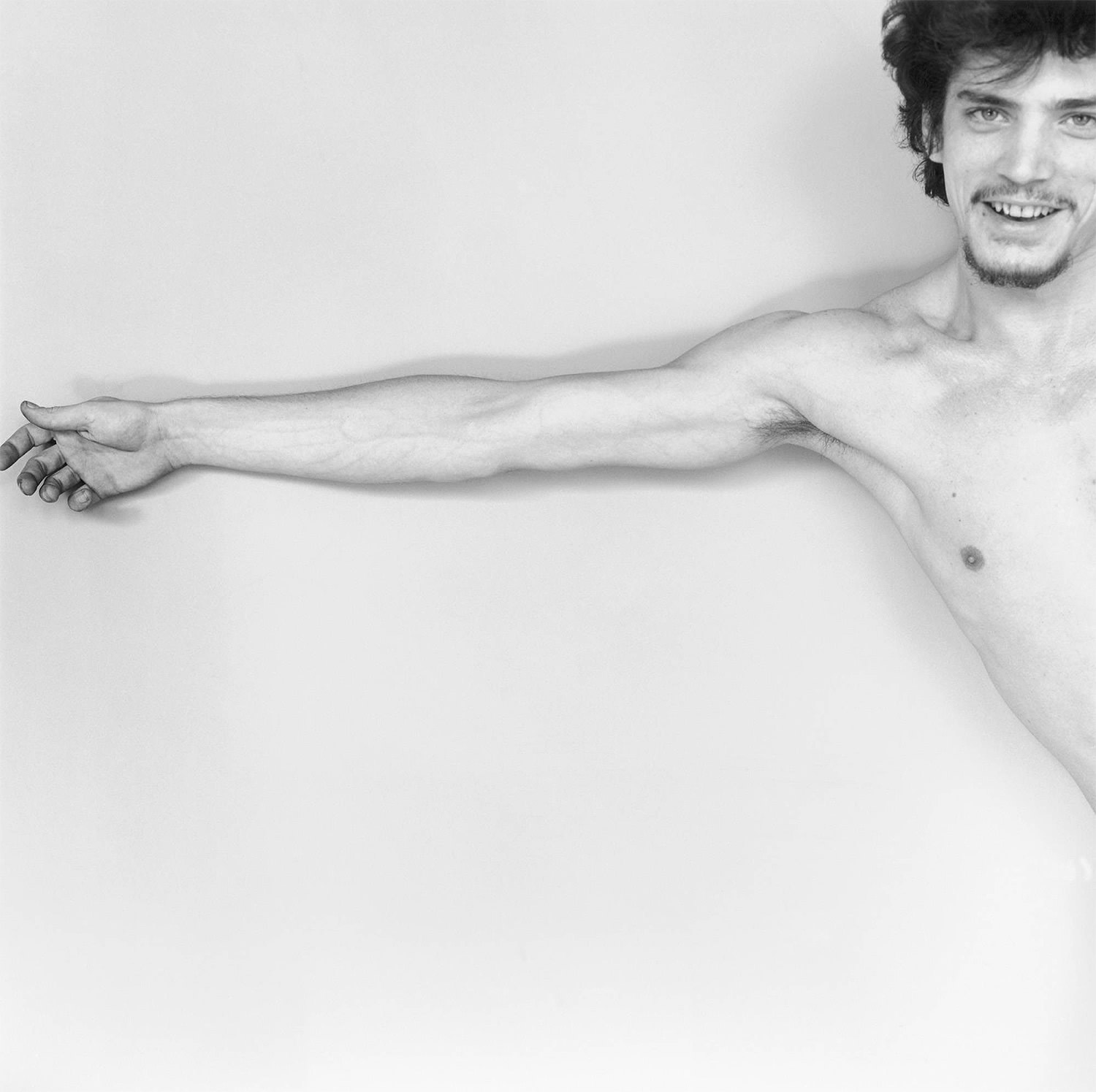

Turning the lens on himself results a chronicle of self-exploration and sexual exploration.

Participatory art-making

Mapplethorpe’s commitment to truth-telling extended past the camera. For real truth, he had to get in on the act. Putting himself in front of the lens, he first experimented with nipple clamps and other implements of pleasure/pain to learn what he liked. Later on his Chelsea loft “had become a port-of-call for men with every conceivable sexual perversion, and they arrived with suitcases, and sometimes doctor’s bags, filled with catheters, scalpels, syringes, needles, laxatives, hot water bottles, rope, handcuffs, and pills. They dressed up as women, SS troopers, and pigs.”

It was important to Mapplethorpe that he have the full experience, and he tested his limits on both sides of the lens. As a participant, he discovered certain personal boundaries, but as a photographer he didn’t hold anything back. The resulting images have an indelibly startling quality.

When Mapplethorpe met Patti Smith, all kinds of sparks flew. The two would remain close friends throughout his life, even as their lives veered apart.

Patti Smith

A strong thread running through Mapplethorpe’s life was his friendship with Patti Smith. They were the same age and had similar artistic vision, and their connection was instantaneous. In 1969, living at the famed Chelsea Hotel, they were surrounded by other soon-to-be-famous artists and musicians. “Everyone had something to offer and nobody seemed to have much money. Even the successful seemed to have just enough to live like extravagant bums.” They hung out at CBGB and Andy Warhol’s Factory. They lived and breathed art.

“Robert believed in me as much as he believed in himself, and it was incredible how much he believed in himself. … He would not rest until he helped me dive down, down, down, and access my confident part. And I did access it, finally. It came out in a funny way, as a performer. But because he gave it to me so early in life, I don’t have to be given it again and again—I just have it.”

At 69, Smith continues to deliver powerful performances all over the world and has published two memoirs, “Just Kids,” about her relationship with Mapplethorpe, and “M Train.”

References: Patti Smith quotes from Vanessa Grigoriadis, “Remembrances of the Punk Prose Poetess,” New York, Jan. 10, 2010. All other quotes from Patricia Morrisroe, “Mapplethorpe: A Biography.” NY: Random House, 1995. See also: Dominick Dunne, “Robert Mapplethorpe’s Proud Finale,” Vanity Fair, Sept. 5, 2013. Christopher Bollen, “Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe,” Interview, Jan. 20, 2010. Images © The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.