Ridley Scott is among the most acclaimed filmmakers of all time, but his landmark work in sci-fi cinema, especially the “Alien” series, is arguable his greatest contribution to movies.

Released in 1979, “Alien” is one of those genre-crossing works which changed both sci-fi and fright flicks forever. A haunted house horror film set in outer space, Scott assembled or was inspired by a range of artists to bring his dark vision to the big screen.

After 1982’s “Blade Runner” Scott wouldn’t work in science fiction for almost thirty years, returning with 2012’s “Prometheus” and following that up with 2015’s “The Martian”—which offered a more realistic trip beyond the stars. In 2017, he went back to the world of xenomorphs for “Alien Covenant.”

Scott’s background in art school and advertising has dominated his movies. He wants each film to look like nothing else out there and be intensely visual experiences. He is a world-builder as much as a storyteller.

Above: Neville Page designed the alien creature known as the “Engineer” seen in “Prometheus” and “Alien: Covenant.”

Primordial, uninviting landscapes have been a major feature of Scott’s sci-fi horror series.

Landscapes

While “Alien” was shot at Shepperton Studios, outside London, in the summer of 1978, both “Prometheus” and “Alien Covenant” made use of exterior locations in Iceland and New Zealand to convey planets far from our own galaxy. The alien planet known as LV-426 (also known as Acheron) was filmed entirely on sound stages and the film’s distinct gothic-horror look heavily recalls Mario Bava’s “Planet of the Vampires” (1966). There is much controversy about this low-budget sci-fi horror’s influence on “Alien” to this very day, but Scott denied ever seeing it. The director has only really spoken about “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” (1974) and “Star Wars” (1977) as direct influences.

Iceland and New Zealand are famed for their barren, majestic landscapes. In Iceland and New Zealand, Scott found primordial settings which encapsulated the otherworldly, the haunting and the frightening. All he had to do was heighten these natural wonders with CG embellishments. It is remarkable, that places on Earth can feel so alien to us.

Costumes in “Prometheus” and “Alien: Covenant” reflect the nature of the missions to alien planets.

Costumes

Realism with hints of the fantastic is Scott’s approach to science-fiction. In “Alien”, the spacesuits were bulky and extensively padded. For the 2012 prequel, “Prometheus” costume designer, Janty Yates, in a 2012 interview with Clothes on Film website described the brief Scott gave to her: “We wanted to go somewhere where it wasn’t traditional spacesuits. Sleek and slimline, to avoid the sort of ‘Michelin Man’ look of the NASA suit.” Interestingly, the yellow piping around the costumes appears to reference “Planet of the Vampires,” which sported a very similar look.

As with “Alien,” the crew also wore individualised costumes reflecting character preferences. Biologist Millburn sports a custom made white hood and vintage spectacles. The crew also wore flip-flops on board the Prometheus craft, as their comfortable and informal footwear. In “Alien: Covenant” Danny McBride’s pilot, Tennessee, wears a straw hat. As with Brett’s Hawaiian shirt and baseball cap combo in “Alien,” the idea—indeed challenge—is for characters to express their own taste in clothing while being part of a crew. Scott’s attention to detail is painstaking.

Spaceships in the film series were designed with input from NASA.

Spaceships

The Nostromo is among the most unusual spaceships in sci-fi history. In “Alien”, it’s basically a truck in outer space. The Nostromo is a towing vehicle filled with ore from floating refineries. It is unglamorous and built for commercial purposes. The Nostromo—named after Joseph Conrad’s 1904 novel—was designed by a combo of Scott’s storyboard ideas and graphic artist Ron Cobb’s drawings. Three versions of the ship were built at Bray Studios, where second unit effects work was completed, to varying sizes, depending on what the shot setup was and what needed to be filmed.

Arthur Max ran the design department for “Prometheus” and returned to Giger and Cobb’s work on “Alien” for guidance. For example, the giant window platform at the front of the Prometheus was initially a design for the Nostromo. Whereas “Alien” was full of practical effects and models, advances in technology meant the ship could be rendered digitally for some shots. The Engineers’ ship, known as the Derelict, was designed by Giger and a similar-looking craft returned in “Prometheus.”

The Nostromo, Prometheus and Covenant look very different, but they do share a commonality, in that each spaceship’s functionality is grounded in realism or close to it. They are commercial vessels and while the theme of intergalactic travel is pure sci-fi, they have been designed to look realistic, and not merely fantastical-looking rocket-ships. The design functionality is key.

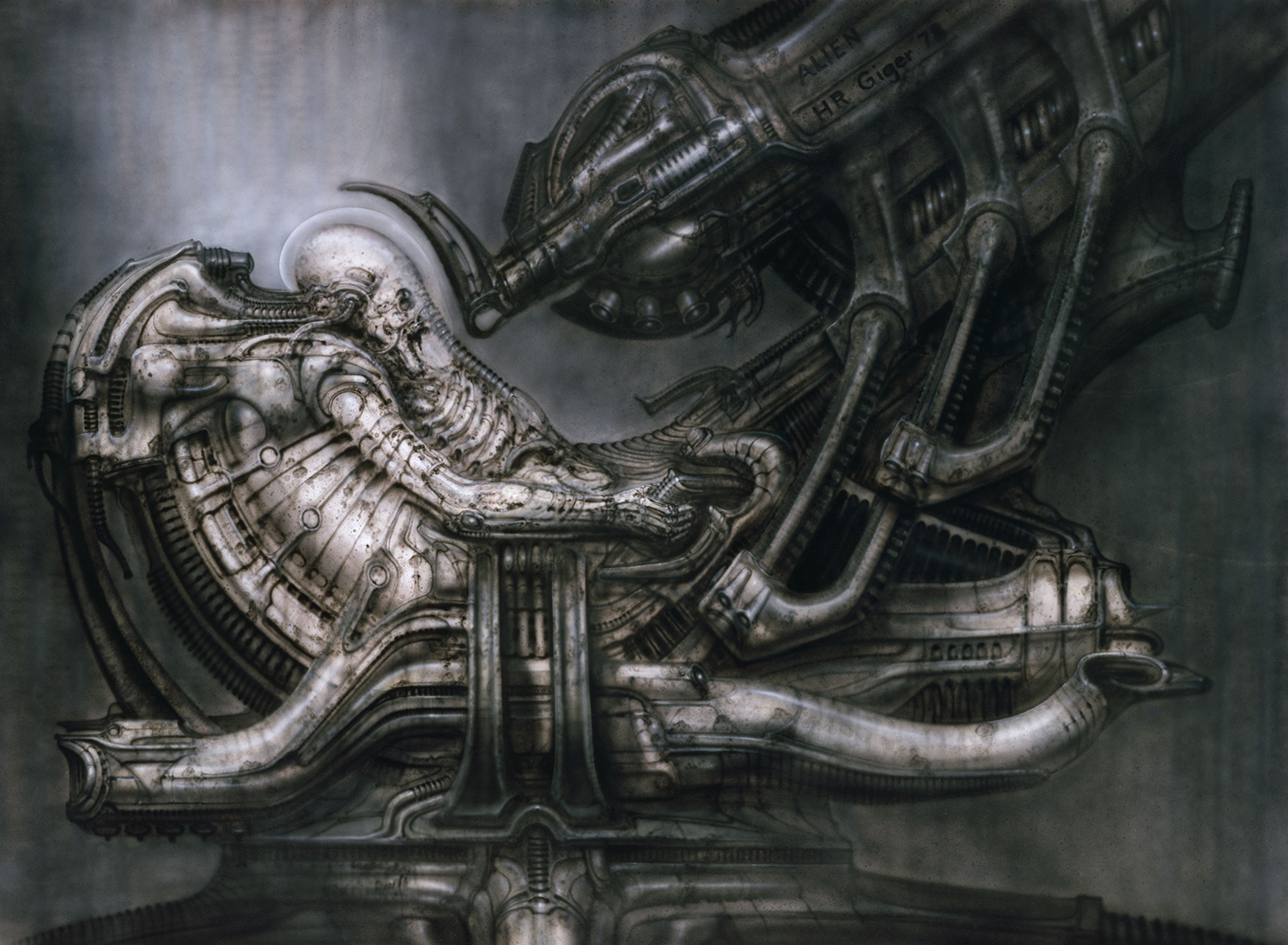

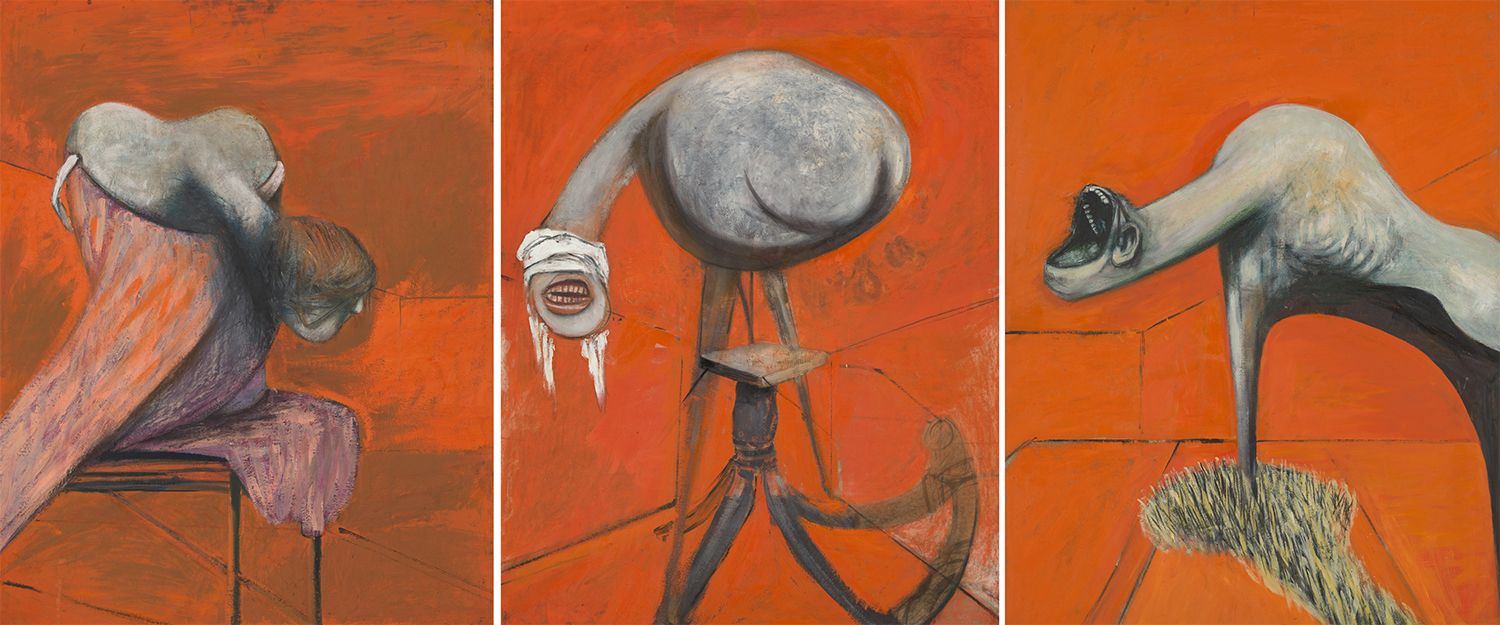

Top: Film still from “Prometheus.” Middle: Art by HR Giger. Bottom: Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion by Francis Bacon, © Tate.

Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger (1940-2014) became involved with “Alien” through screenwriter Dan O’Bannon. The American was hired by Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky to adapt Frank Herbert’s “Dune” for the big screen, with Giger on board too, as a conceptual artist. When that project famously fell apart, “Alien” writer O’Bannon remembered Giger’s erotic, bio-mechanical creatures and gave Scott a copy of Giger’s art book, “Necronomicon” (1977), which sparked off the director’s imagination. Giger was hired to provide conceptual drawings for what was known as the “star beast” and several significant sets (such as the derelict spaceship carrying the alien eggs and the “Space Jockey” character). The alien, later known as the xenomorph, was inspired directly from Giger’s “Necronom IV” painting. Giger won an Oscar, along with the rest of the Special Effects team, for his work and created one of the most enduring icons in horror cinema. “Alien” and the sequels owe a lot of their distinctness to Giger and Scott’s decision to hire him.

The infamous chest-burster creature, however, took inspiration from Francis Bacon’s “Three Studies for Figures at the Base of the Crucifixion” (1944). The original design by Giger was deemed unsatisfactory, leading Scott to re-design the monster into something phallic-shaped and remembered Bacon’s surreal painting, which provided an image to work from.

Movie stills © Twentieth Century Fox | HR Giger artwork © HR Giger & Titan Books