Stephen C Stratton, a youngster in the late 1970s, tattooed his buddies with a popsicle stick and taped sewing needles. At The Needle Master studio, he got his first professional tattoo, a Lambretta-scooter motif connected with the Mod revival subculture.

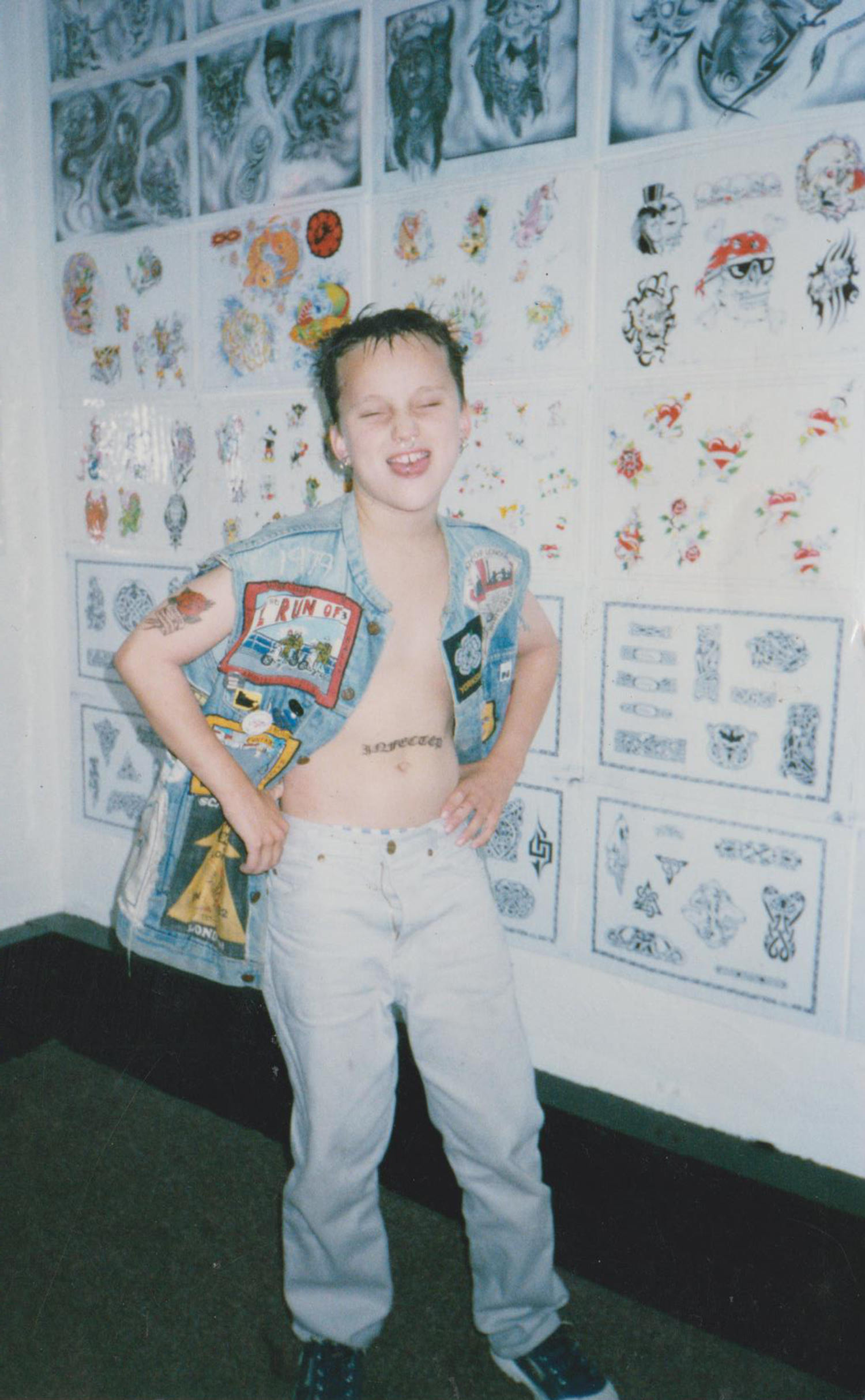

Stratton joined the military and became a nurse a decade later. Because tattoos were frowned upon in the medical field, he began covering them with long-sleeve shirts. He continued as a health care professional until 1996. Then, along with his nephew Marc Newton, they opened the World Famous Skin Sorcerer tattoo and piercing studio in England.

Stratton is currently an anthropologist and PhD student at the University of Essex, learning under the direction of Dr Matt Lodder—a senior lecturer in art history and theory and director of American studies. Stratton’s research focuses on Coptic Christianity and its significance to pilgrims who seek to adorn the ancient and historical Coptic tattoo. But before we get further into this topic, it is essential to understand Stratton’s journey.

These wooden blocks are templates for Coptic tattoos and are from the collection of the World Famous Skin Sorcerer.

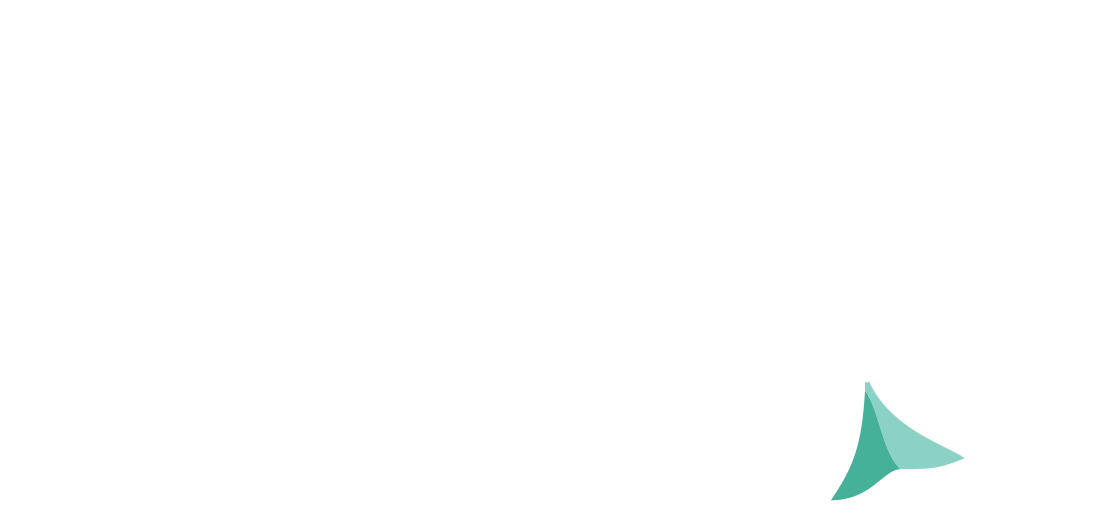

Stephen C Stratton, his son Joe, and his then-partner Sarah.

I am sorry for your loss. I would like to know if you are willing to talk about your son Joe, what mental health issues he was facing, how old he was, and when he passed away?

Joe’s mother, Sarah, and I met in 1983 when we were nineteen and student nurses. We lived in the nursing home on hospital grounds. During a sabbatical, we traveled to Holland together, and Joe, known as Joe Boy, was conceived whilst we were in Amsterdam in 1986. I was so happy to become a father, and although Sarah and I separated soon after, we both enjoyed equal contact with our only child. By the time Joe had reached high school, he was already showing the first signs of mental illness (depression and anxiety); this sadly escalated to drug addiction, and after that, Joe and I struggled to manage, as, for years, I desperately tried to find him happiness. Seeing Joe suffer was unbearable, and being powerless to help was the most difficult thing to understand.

I was to become his full-time carer until his death; such was the extent of his illness. It was not unusual for his mother and me to be concerned about Joe’s welfare, and in the days before his overdose and death, Joe had been arguing with his partner, and she had ended the relationship. I met his mum at his flat and checked on Joe, as we so often would. I knocked on the door, and mum shouted, “Joe.” We looked at each other, and I just knew. I barged the door open, breaking the lock, and we ran into his flat to see our beloved Joe Boy lying on the floor. It was September 4th, 2018, at 9.30 pm. My world ended at that moment.

Left to right: Stratton’s colleague and him as medics in South East Asia, 2005.

Although both Joe’s mum and I are qualified nurses and I had been a volunteer medic in disaster-hit South East Asia, dealing with hundreds of wounded and dead, nothing at all can ever prepare you for finding your child dead.

Joe was just 31 years old.

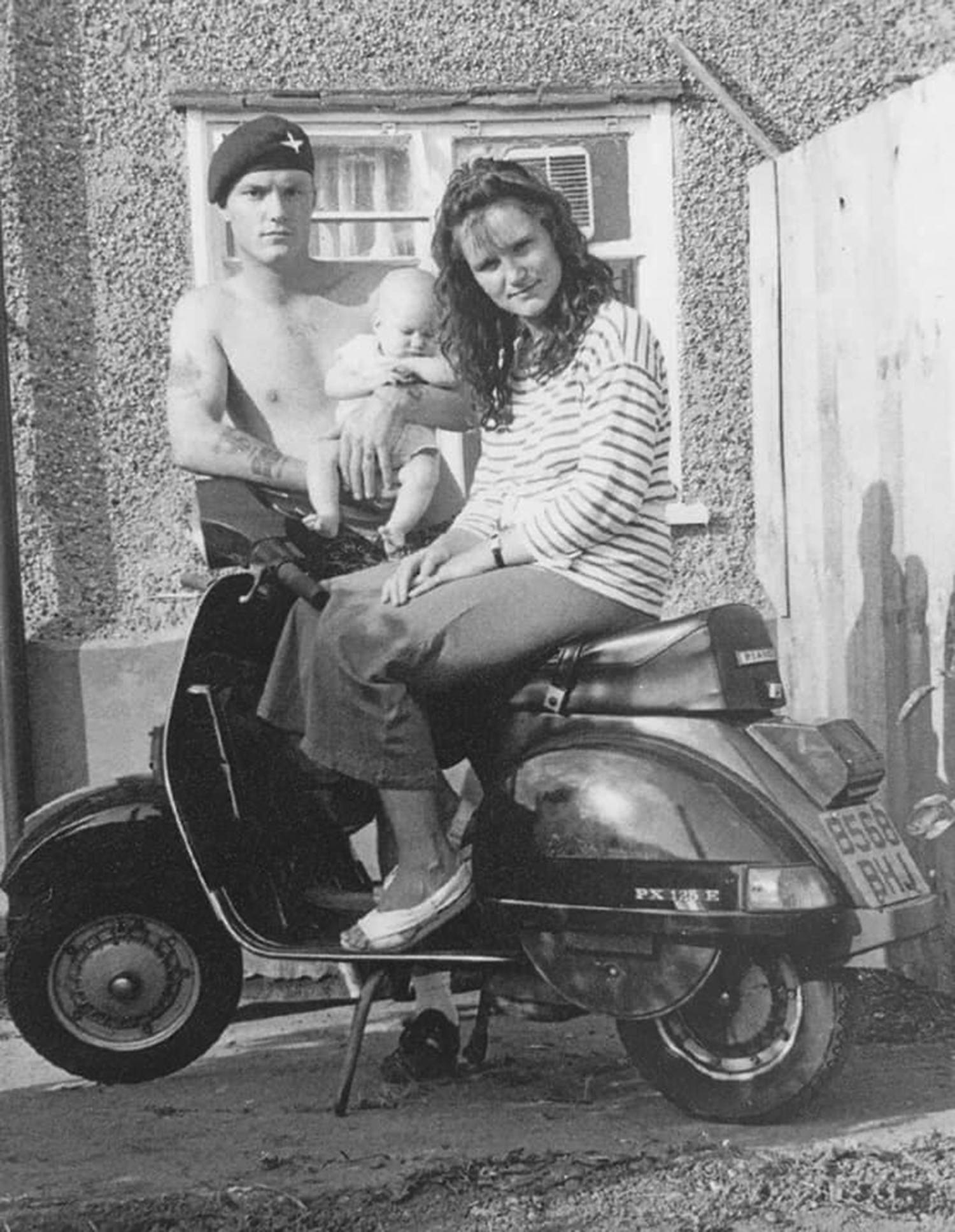

Joe Boy, 10 years old, in The Skin Sorcerer studio, sporting his father’s gang cut.

When Joe passed away, you spent most of the year in your apartment struggling with PTSD. What motivated you to get out of the house?

Eventually, I took long cycle rides, and I visited every place I had ever been with Joe. Every youth club, school gate, cinema, fast food restaurant, park and into his adulthood, all the pubs and places we went together. It took me a year to complete. On route, I would collect white feathers, believing they were a sign from Joe. I have jars full of feathers at my flat; they are everywhere and will always be with me. Sometimes when I am still distressed, Joe sends me a sign. It’s the hope I lost when we found him. I have had so many signs, I know they are Joe; they are just too unbelievable not to be.

Marc and Tanya Newton, and Stephen C Stratton, from left to right.

One day I cycled to see my nephew Marc and his wife Tanya at the World Famous Skin Sorcerer (the studio we had opened in 1996). Marc suggested I come back to the shop to get out and be with people. And so, I started the long and indescribable painful journey of recovery. One that will never fully happen, and that’s the most challenging thing to accept, that this is it, this is the profound emptiness I will forever hold inside. I get some comfort from writing to Joe on social media. I sit on the beautiful memorial bench we had placed for him at his favourite park, and I chat with him and tell him what I’m doing, what is happening in the world and chat about the things we did when he was with me in person.

Stephen C Stratton, tattoo anthropologist, 2021.

Have you gotten tattoos in honor of your son?

My boy had a tattoo of a Trident on his face. To this day, I don’t know why he had the tattoo, or what it meant to him, or who tattooed it. I have asked his friends, and no one seems to know. It’s a mystery I would love to solve. When I returned to the studio in 2019, Will Mant (from Skin Sorcerer) inked the same tattoo in the same place on me.

Marc Newton, owner of the World Famous Skin Sorcerer and Razzouk Tattoo’s official UK ambassador.

Marc and his wife have been supportive. Who else has helped you?

Marc and Tanya have been incredibly supportive, as have Will and Dave, the other tattooists at the tattoo studio. I enjoy going there, and now it has other significance within research; it keeps me focused. I hope so much to visit Jerusalem and Razzouk Tattoo once the global pandemic relents. I often reflect on where I might be had I not revisited the studio that day. The support I have had is immeasurable from Marc, the studio, Tanya, and Janice.

The larger central cross depicts Jerusalem, while the four smaller crosses represent Christianity spreading to all four corners of the earth.

You have found a purpose in terms of tattoo studies.

In the same year my son passed away, Marc visited Jerusalem and worked at Razzouk Tattoo in the Old City. Razzouk has such a historical significance within tattooing, ancient history, the arts, and archaeology. I had researched the history during my time at the School of Oriental and African Studies.

Marc Newton tattooing in Maldon, Essex, England.

Wassim Razzouk (the current family traditioned owner) then offered Marc a unique and exciting opportunity to become an official Ambassador to have the honour of tattooing the Coptic Christian designs, using replica wooden blocks and outside Jerusalem for the first time in Razzouk’s 700-year-old history.

It was a combination of my previous interest in religious tattooing and Marc’s encounter with Wassim Razzouk in Jerusalem that led me to further my research. I’m now a PhD student at the University of Essex, seeking to discover “what it means for humans to be tattooed.” I am in a unique position to embrace this research, having access to potential pilgrims visiting the studio in the UK and hopefully with further fieldwork being undertaken in Jerusalem.

Although legend has it that St. George slays a dragon, the artwork depicts him slaying a crocodile.

Tell me more about Coptic tattoos.

For centuries the Razzouk family have used small wooden blocks that serve as a stencil for the tattoo, each one hand-carved from Olive wood; some of the blocks have survived for hundreds of years. The blocks were first extensively documented and catalogued in 1958 at Razzouk by historian John Carswell.

As a minority and often persecuted religion, the Coptics do not see their tattoos as a fashion statement. Still, an indelible and defiant mark of their faith, frequently placed on the inner right wrist, identifies the pilgrims as “Copts” and allows them access to their often heavily guarded churches.

More Coptic-tattoo blocks from the UK studio.

You had mentioned that you are studying “what it means for humans to be tattooed”; have you entirely figured it out?

It is a question that I believe can never be fully realised. I have studied, researched, and worked with humans my entire life. We are a complex species, complicating everything in our lives, and yet we are continually evolving. As anthropologists, we are still striving to find “what it means to be human.” I don’t think I will ever truly discover what it means for “humans to be tattooed,” the possibilities are endless. For some, it’s so often a personal journey, culminating in a cathartic experience that remains with you forever. It is where you were in life when you were tattooed, not simply the location or the studio, but where you were in life at that moment. It is about who you shared that experience with, those memories you can share with others, and those memories you chose to remain with you.

Despite its ever-increasing popularity, being tattooed remains a unique and wonderful moment that can never be taken from you. Is this what it means for humans to be tattooed?

Vintage photos © Stephen C Stratton All other photos by Will Mant