All around the world, artists with physical and developmental disabilities are using their art practices to share their experiences and produce raw and exciting new narratives of acceptance and adaptation.

Throughout the history of art, however, disability has not always been represented favorably or ethically. As Claire Cunningham—a choreographer and dancer who was born with osteoporosis—observes, in the sketches of Medieval artist Hieronymus Bosch, disabled people are drawn and identified as “beggars and cripples“—a pejorative coupling of marginalized traits that some academics say is related to historical understandings of sin. This type of judgment of what a “fully-capable” and “healthy” body is has trickled down into modern thought; Sue Austin, who uses a wheelchair, points out how people commonly associate wheelchairs with words such as “limitation, fear, pity, and restriction.” These assumptions can be very damaging to a person’s self-concept, and indeed, it hinders humanity’s ability to embrace the empowerment and beauty that comes with acknowledging different ways of seeing and being in the world.

All of the artists featured here face physical and/or developmental adversities—some that they’ve had from birth, and others that arrived through accidents or infections. Nevertheless, they bravely use their unique ways of accessing the world to create art and tell their story. And while it’s not without pain or an acknowledgement of limitation, expressions of difference are a powerful force, creating freedom and fostering acceptance, respect, and support.

By scuba diving in a wheelchair, Sue Austin provides a healing new perspective on movement and ability.

Sue Austin

Sue Austin is a renowned multimedia, installation, and performance artist who uses her wheelchair in creative ways to shift perceptions of disability. As the founder of Freewheeling—a disability-led art initiative—she believes strongly that disability arts hold a “secret,” that if explored, “can act to heal the divisions created in the social psyche by cultural dichotomies that define the ‘disabled’ as ‘other’.” She is well-known for “Creating the Spectacle!” (2012), a project involving live art and film where she used a modified wheelchair to dive underwater. Moving freely and gracefully in a three-dimensional space, Austin conveys to viewer the joy and excitement she felt when she received her wheelchair (what she calls her “powerchair”) after being paralyzed following a long illness. By doing so, she also challenges what we think is possible—or not possible—when it comes to different bodies and abilities. By writing “new narratives to reclaim [her] identity” from societal misunderstandings and judgments, she encourages healing and freedom.

Being deaf has not stopped Andrey Dragunov from becoming a master of dance and finger-tutting.

Andrey Dragunov

Andrey Dragunov is a twenty-four-year-old Russian mover based in Saint Petersburg. Born deaf, he expresses himself through innovative dance. Since the age of fifteen he has practiced “finger-tutting,” a new style of street dance (usually linked to the hip-hop community) that focuses on the fingers; it resembles a form of sign language, but instead of words, the hands create interpretative shapes and symbols that pulse and flow along with the music. Finger-tutting is quite mesmerizing to behold, as Dragunov shows us in the video above. “My hands do not rest,” he says. “I am always working to come up with something new.” By creating a visual experience of the musical beat through the body, Dragunov shows us the power of dance to not only transmit messages, but to simulate sound.

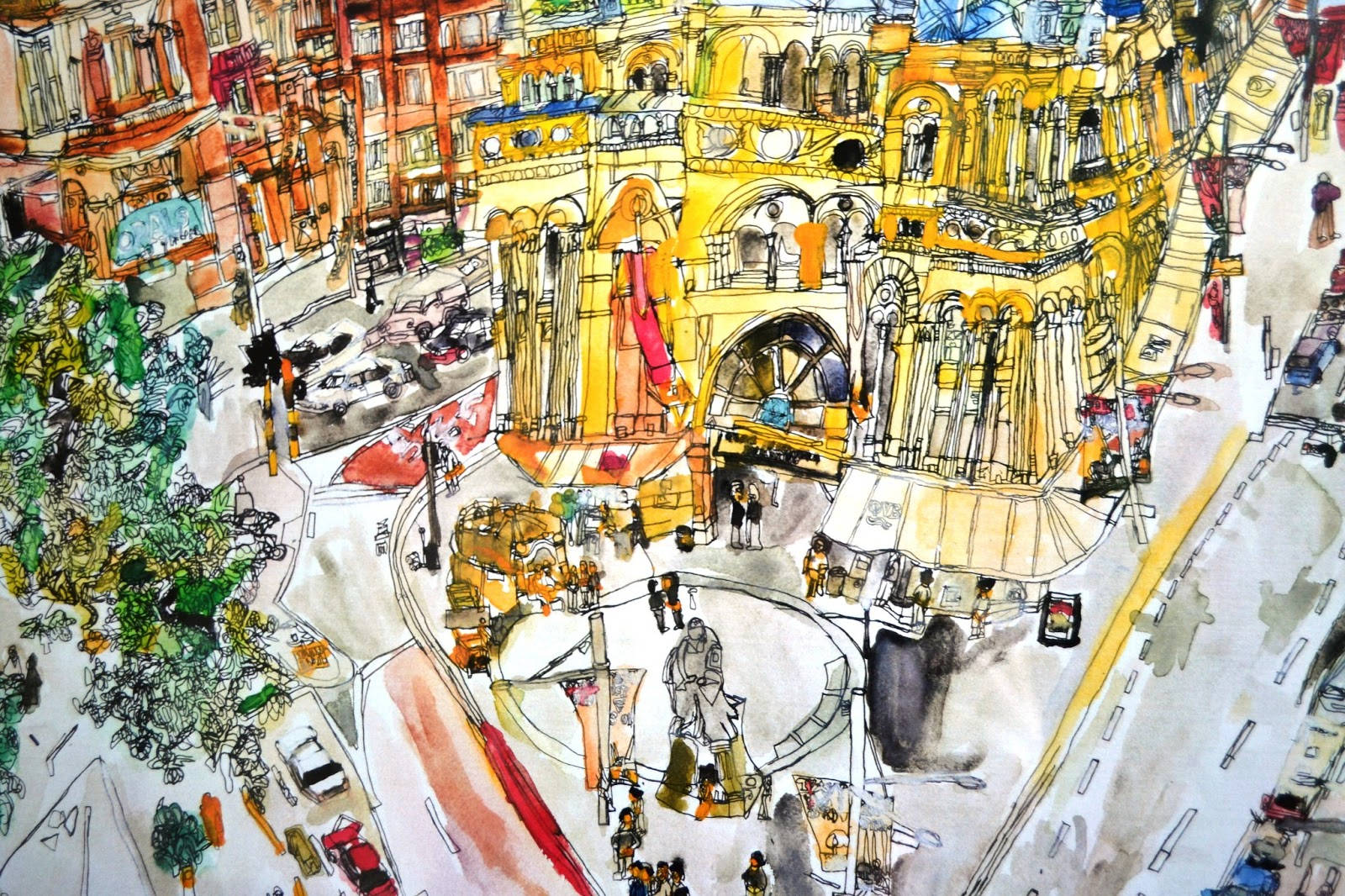

Ping Lian uses art to communicate his experience of the world.

Ping Lian Yeak

Lines and colors dance in the joyful artwork of Ping Lian Yeak. When he was just eight years old, he said, “I want to be an artist.” Born with autism, he avoided physical contact and struggled to communicate while he was growing up. With the help of his mother and art teachers, he learned how to trace and then to draw. Now, at the age of twenty-three, he is recognized as a prodigious artist, with a growing body of work that has been exhibited dozens of times. His works depict urban centers around the world, capturing the grandeur of the architecture and the energy of the people. As the art critic John McDonald has has observed, painting has become a second language for Ping Lian, and his “cheerfulness and openness of heart are apparent at a glance.” With a bright future ahead of him, Ping Lian has overcome adversity by channelling a passionate creative outlet, making a name for himself as a lively contemporary artist.

After suffering as an innocent bystander of a random shooting, Mariam Paré taught herself to paint in a unique way.

Mariam Paré

Mariam Paré is an artist and advocate for people with spinal cord injury. When she was twenty years old, she was struck by a bullet in the back of the neck during a random shooting; the shooter was never found. For the first year after her injury, she found herself lost in a maze of confusion, blame, depression, and suicidal thoughts. She started painting upon getting out of rehab, but because her hands shook so much, she began using her mouth to hold the paintbrushes. Because not much is written on the technique of mouth-painting, Paré taught herself by trial and error, developing a technique that allows her to create her vibrant style of portraits and sun-filled scenes. While some of her paintings are dark, they are far and few in-between, because Paré wants to convey the joy that painting has brought her. Now, seventeen years after the tragic incident, she is happy to be an artist. Referring to her particular skill of mouth-painting, she states that in a competitive art world, “it is a niche I want to fill.” When she’s not painting, Paré shares her story with audiences, “teach[ing] people of all ages how to turn adversity into opportunity and to live the abundant life.”

“Walking with Angels” (top) and “Shadow Poppies” (bottom) convey Holder’s emotions and transformed world views.

Holly Holder

For almost 30 years, Holly Holder (previously Debbie Holder-Ross) worked internationally as a makeup artist on various film and TV sets. In 2000, she was diagnosed with Retinitis Pigmentosa, an inherited degenerative disease that meant she would eventually go blind. By 2014, she had to stop doing makeup due to vision loss. After a period of depression, in 2015 she picked up her paintbrushes; she also changed her name to “Holly” to help her let go of her depressed identity. Painting brought her a sense of peace, and in October 2016, she had her first exhibition, meaningfully titled “Out of the Dark” (hosted by Art in the Mill in Knaresborough). Characterizing her work are misty landscapes infused with emotion, inspired by places she’s lived, such as Valencia in Spain and her current home in Harrogate, North Yorkshire. Just as she has bravely adapted her life and identity, she has also adapted her style; as stated on her About page, “being freed from detail, [Holder] now has a bigger perspective, seeing in colour and form—a metaphor for how she feels about life as a visually impaired artist—creating paintings filled with energy, colour and movement.”

Claire Cunningham’s “Give Me a Reason to Live” poetically demonstrates what her body can and can’t do.

Claire Cunningham

Claire Cunningham is a performance artist based in Glasgow, Scotland. Self-identifying as a disabled artist, she incorporates her crutches into her work, using them to express her own physicality and expand the definitions of dance and dance techniques. Her solo shows are powerful, vulnerable, and illuminating, based on her real experiences and deep personal questions. In the video shown above, Cunningham describes the driving inspirations behind “Give Me a Reason to Live” (2014), a performance inspired by Bosch’s aforementioned depiction of “beggars and cripples.” Not only does she use her crutches to convey what she is capable of, but courageously, she shows what her body cannot do: she cannot stand without them. “The reality as a disabled person and other marginalized identities is that you have to prove how capable you are,” she says in the video, “but also show your feelings, also show what you can’t do in order to prove your validity, or the validity of your claim to the support that you need to exist.” In addition to sharing her story, she also seeks to encourage other disenfranchised people to use dance outside its strict definitions to express and explore themselves.

“Flatiron Building” (top) is a prime example of Jessica Park’s incredible use of pattern and color.

Jessica Park

Jessica Park is a self-taught artist with autism. Her mother, the late Clara Claiborne Park, was an author who wrote extensively about her daughter’s experience with autism, pioneering work on the subject in the late 1960s, when it was still largely misunderstood. Jessica herself is represented by Pure Arts Vision, a studio gallery in New York that provides space, support, and opportunities for artists on the autism spectrum. Her work is characterized by detailed paintings of architecture set against vast, meditative backdrops, inspired by the artist’s love for Victorian architecture, city skylines, and astronomy. As Tony Gengarelly points out in his article on her work for Brut Force, “[Jessica] has refuted the old ghosts of misperception that artists with autism just render what they see, repeat endlessly the same subjects without imagination or creative insight and never evolve as artists”; rather than repetition, every piece she creates is daring and unique, experimenting with different forms, backgrounds, and compositions, reflecting a highly driven and original mind. Her art career continues to blossom with various exhibitions and publications featuring her work.

The top image was shot by Craig Barritt for Smirnoff’s “We’re Open” campaign. © Getty Images.

Chris Fonseca

“Dance is not an option, it’s who I am,” writes Chris Fonseca, a London-based street dancer. He became deaf as a child due to meningitis and now wears a cochlear implant in one ear. Nevertheless, he never stopped dancing throughout his youth, and eventually joined an all-deaf dance group named “Def Motion,” and later the Studio 68 dance training academy. “My creative process is different from a hearing person’s—they absorb it quicker,” says Fonseca in a video by Noisey on his collaboration with Smirnoff, shown above. To get into a dance, he first has to feel the vibrations, then merge the beat with the sounds he can detect using his cochlear implant. “Then the music takes over and I become part of it,” he says. By finding a way to express his passion and never giving up, Fonseca hopes to encourage other deaf dancers to keep pursuing their dream, for “a deaf person can do anything except from hear.” To see videos of him dancing and teaching, visit his YouTube channel.

Lisa Bufano’s stilt-legs give her locomotion an animalistic, almost insect-like quality.

Lisa Bufano

Lisa Bufano (1972–2013) was a visual artist, performance artist, and a dancer. When she was 21, she lost most of her fingers and both of her legs below the knee to a staph infection. Despite this tremendous change in her anatomy, she never stopped making art. She sewed fabric sculptures, took self-portraits, and when a professor studying the lives of amputees discovered her, she began her career as a performer and dancer. “I feel like I have lots of different bodies,” she said in the video above. “I think [my] experience made me think that it’s actually an opportunity to make different prosthetics for performance.” Among her many limbs were 20-inch wooden stilts, aquatic fins, and aerial suspension ropes. The way she moved was hypnotic, unsettling, and endearing all at once. “I want to be seen as attractive and beautiful and sexy like everyone else,” she said. “But I think that in my artwork, for me, it’s trying to find some comfort with being everything a human can be.”

Her loss is a tragedy. Speaking of her death, her brother Peter heartbreakingly wrote, “I believe [Bufano] lived her entire life and that her life was many lives. I don’t believe it was cut-off short. Her mission was completed and she must have understood that fact when she departed from this world.” And while it is not our place to speculate on her departure—Bufano herself felt that journalists often got her story wrong—she left a profound mark on the world, demonstrating with fierce vulnerability an alternative range of motion that people are capable of.

Images © respective artists