On my way to Charlie Cartwright’s home in Modesto, California, I was excited to be conducting a rare interview with the pioneer of single-needle tattooing.

Cartwright (plus Jack Rudy and Freddy Negrete) changed the tattoo scene’s course; better yet, they helped build it to what it is today. All of them were inspired by 20th-century penitentiary-like black-and-grey tattoos and refined them to a mainstream level.

Here, I am sitting on a brown sofa in Cartwright’s living room, looking around at the Christian crosses hanging on the walls, native American sculptures on the floor, and tons of “Good Time Charlie” memorabilia and merch stacked on one side of the room. He still goes by the name “Good Time Charlie” (which he autographed on a poster for me), the alias meaning a carefree and social person, which fits him perfectly.

Cartwright’s neck tattooed with a Polynesian-style pattern, and his tattoo sleeves on their 5th layer of black ink making it hard to depict the forms, but he was happy to have covered up older work, telling me, “there was nothing wrong with what was there.” His hands are also heavily tattooed with religious crosses and the words “hold fast” on his fingers—the latter suggesting “to bear down and fight through the storm” like the sailors would use, or relating to the bible “to hold your position, or fix your gaze and not lose sight of.” Cartwright’s faith has always been present, guiding and balancing his career and personal life.

Above: The tattooed hands of Charlie Cartwright. Photo © Adriana de Barros.

2021—Charlie Cartwright in his home in Modesto, California.

You started tattooing when you were 15. Your father found out and got extremely mad. What happened?

He disagreed with it, didn’t like it, or go along with what I was pursuing. One day, my dad woke up my brother and discovered that he had three tattoos [done by me]. My brother was ten years old [and I was 15]. He got really mad about it and told me, “Don’t ever put another tattoo on him.” And so I was threatened not to do that again. After that, I didn’t come home often because he didn’t like what I was doing. Well, unknown to him, probably a year or two later, I think I was 17, I came home to eat a good meal and see my mom … I walked in the kitchen, and I ended up in the dining room—my father gave me an uppercut that wouldn’t quit. I slid down the wall, and he said, “I told you not to put another tattoo on him!” My dad had seen another tattoo on my brother’s leg (one that he hadn’t seen before), and that’s why he did what he did to me. And I said to him, “Okay, I’m leaving!” So I left and went back [somewhere in the] neighborhood, and two weeks later, he came to tell me, “Your mom wants you to come home.” And I said, “Yeah, what about you?” And he said, “Yeah, I want you too.” And I asked, “Are we ever going to talk about tattoos? Because I don’t know how to explain it, dad, but I’m just going to dig them until I die.” And that was that.

Your father was a pastor.

Yes, he was a Pentecostal preacher for 47 years with one organization. He was probably a preacher for 60 years of his life.

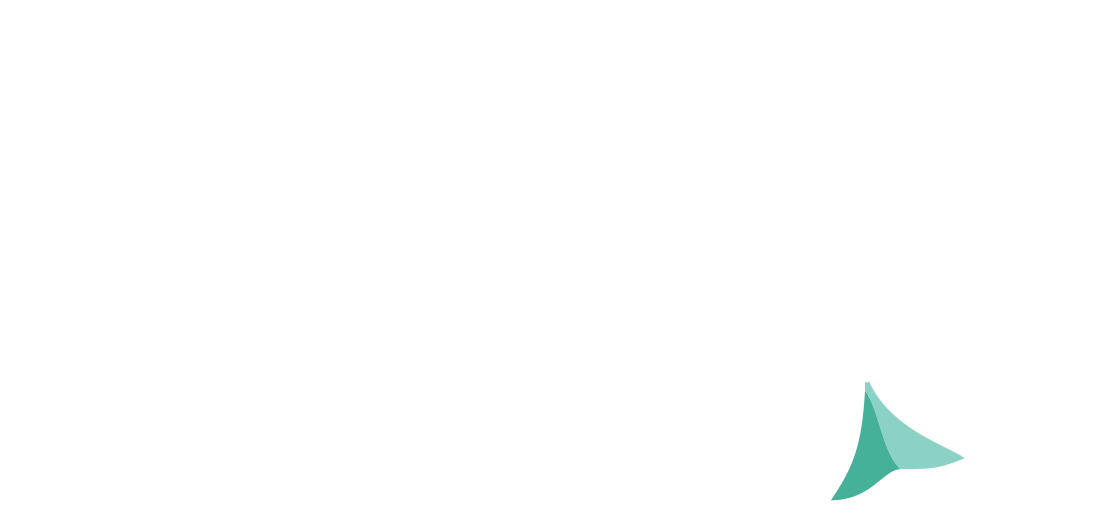

Religious tattoos and drawings by Cartwright, published in book “Tattoo Man.”

Because of him, did you rebel against religion when you were young?

Well, I never did rebel against religion. Except for my dad’s standpoint, he thought that it was what they called “practicing legalism,” by expressing his desire that tattoos weren’t cool because of something written in Leviticus 19:28, which is “Do not cut your bodies for the dead or put tattoo marks on yourselves.” But as I have discussed with other people, we’re not Jewish, and we’re not subject to the Levitical Law. We’re Gentiles, and we live under grace as Christians. And so that was my difference, the difference in my opinion. And besides, even though we memorialize our loved ones on our skin, we’re not doing it, cutting ourselves to appease false gods, to remove our loved one from some state of purgatory or limbo.

Did you ever forgive your dad for giving that uppercut?

Oh yeah. I never quit loving the guy. I just knew it was his knee-jerk reaction to what I had a passion for.

Cartwright has been married for 58 years and has a great relationship with his three kids.

Did he understand your passion for tattooing later in life?

Even though he accepted it and resigned himself to it, I don’t think he ever fully appreciated it. After 25 years of tattooing, he said: “Son, I never make it my business to make your business my business, but you sure spend a lot of money!” “What do you mean I spend a lot of money?” I said. (My dad was dirt poor as a kid.) “Well, you and your family fly all over the place. You live so wildly. I don’t quite get that. Can you give me a ballpark of how much you make?” And so I told him, and his eyes just bugged, “That’s more than the president of the United States makes!” “I don’t know what the president makes, and I don’t care.” But anyway, I think he appreciated the success because he measured everything in dollars. Which I had financially, but I don’t measure happiness by money.

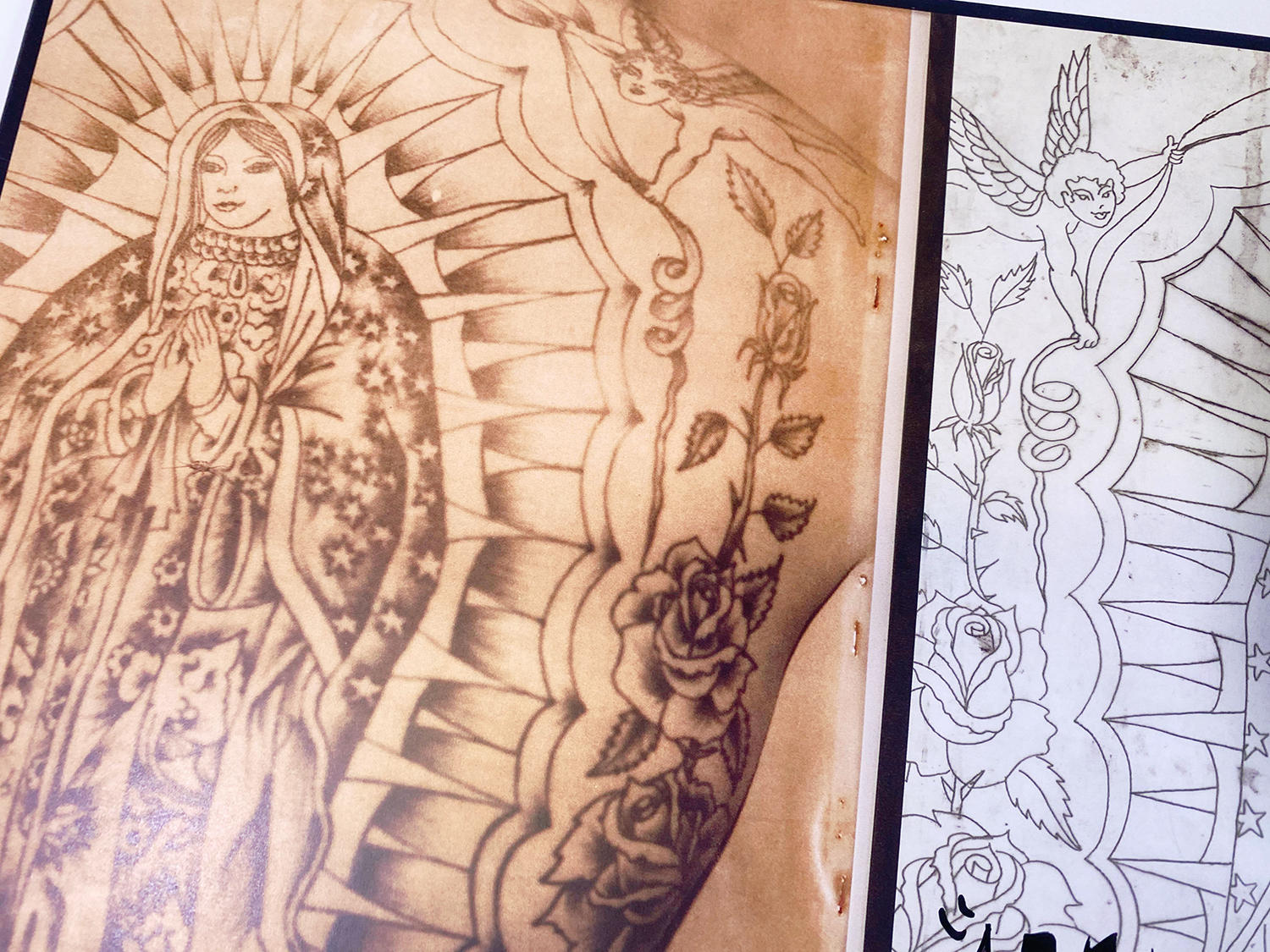

Snapshots of Jack Rudy in the late 70s. Photos from “Tattoo Man” book.

When Jack Rudy first met you, he was 19; he thought you were a biker. Were you?

Well, no, I never was a biker. I did buy a trike from Lady Blue who worked for me in East LA. She said she would sell it for $1500. I didn’t even want a trike, but because she had spent $4,500 on parts and many of the Hells Angels had built it for her, it was cool looking. I rarely ever rode it because I would be mobbed by people wanting to talk about it.

Cartwright and Rudy book signing at the Golden State Expo in 2020.

You mentored Jack, you worked together, and you still attend events simultaneously. How does it feel to have a lifelong friend on this journey?

It has been a good thing for both of us. I still talk to Jack often, and we get together periodically. I have absolutely no regrets for breaking the guy in because he’s made a major contribution to the industry. He wasn’t just another person that liked tattoos; I could tell that Jack had talent! So he became more than just a guy that you break-in and go on down the road. We’ve been friends for over 45 years.

That’s also why I decided to do the book with Jack, “Tattoo Man—The Story of Good Time Charlie’s.” Our history is so connected. The fact is I never started [gave apprenticeships] to hardly anybody in the business. Jack is the only one of three people that weren’t relatives. And my only relatives were my children, that I ever broke in, all three of them tattooed at one time, and only one remains. But Jack, he was a good one. He’s carried on the name big time [“Good Time Charlie’s Tattooland”] and contributed greatly to the legacy of a black-and-gray fine line.

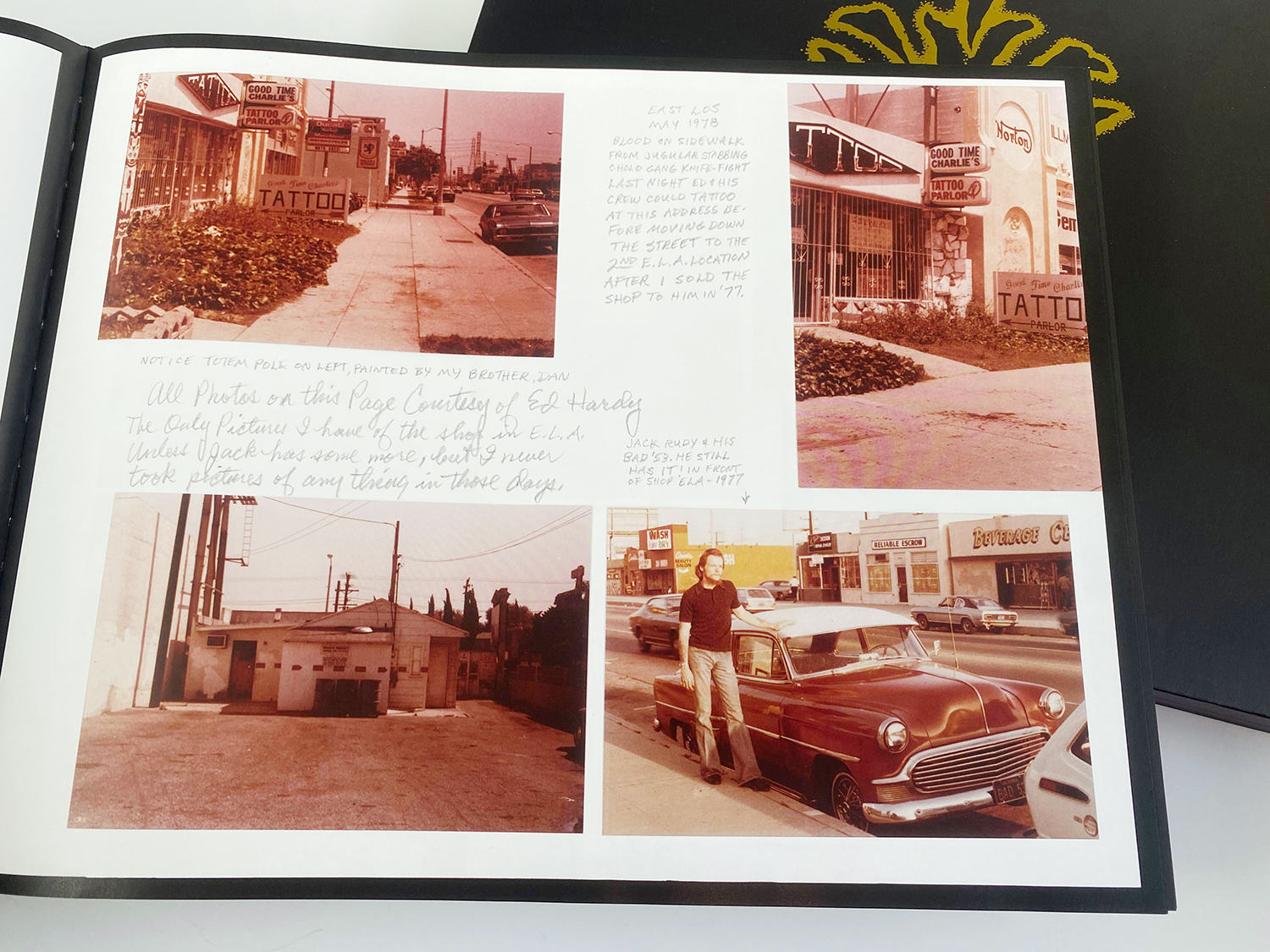

Cartwright’s tattoo shop was purchased by Ed Hardy in 1977. Photos © Hardy.

You were a visionary for opening a tattoo shop in East Los Angeles in 1975. You worked long hours, as you stated, “Till the last dog died.”

Sometimes we would finish at 7:00 in the morning. We would only open from 5:00 PM until 1:00 AM. I think I had been open for about a year, when Lady Blue (who worked with me at The Pike), phone calls, “Hey buddy, I went by your shop, and the sign says it opens at 5:00 PM. What’s that all about? How come you are not opening at noon?” I said, “Well if you want to open it at noon, you open it; I don’t want to go in until 5 PM. I like the night shift.”

The entrance to The-Pike-amusement-park in Long Beach, California.

The Pike’s appeal was the later hours—carnival and amusement park.

Exactly!

Lady Blue said later, “I just had a visit from the health department today, and they said, ‘Well, we never got in there in all those years because we went home at 5 PM.” And so anyway, I thought, I figured that part right. But it wasn’t because of that; the later schedule worked better for me.

Presently custom tattoo art is typical; however, 50 years ago, it wasn’t.

It wasn’t that I was trying to do anything unique. I was trying to do whatever the customer wanted, whether it was unique or not.

When I first came here [to California], all the tattoo shops I went into, they were like pick something off the wall, or we don’t have it. And I thought, “why can’t you have anything you want?” So I would do portraits of the customer’s wife sitting beside them in East LA. And I’d look at them and draw it on them. I used to stand out in the sun and directly draw their van or motorcycle on their arm—that was the real art to me. That’s how I always did it as a kid. I didn’t even know what stencils were. I never even heard of paper stencils or any kind. I just used a ballpoint pen.

That was very innovative at the time. Ed Hardy also did custom, freehanded pieces.

Yes, me and Ed were kind of on the same trip, but he was on a much higher appointment-only type basis and doing larger works. Well, I would do anything the customer wanted—i.e., smaller pieces. It was walk-ins all the time, having to approach as a street-shop tattooer.

Although he is known for custom art, he also has done plenty of tattoo flashes.

Did you ever think the tattoo industry would become this massive?

Personally, no. No idea at all that it would expand beyond where it was, meaning there were only half a dozen shops, maybe, at the Pike and Long Beach, and two or three in the Los Angeles area, period. One in Van Nuys and one downtown. And there just weren’t that many shops around. And at one point in time, you could look at anybody’s arms and tell them, “Hey, you’re from Philadelphia, or you’re from New York, and so-and-so did that tattoo,” and they’d all wonder how you knew that. Well, there were only probably 300 tattooers in the whole nation.

It was easy to distinguish.

Yeah, there were so few; you just became familiar with everyone’s styles. Right now, even Little Annie that lives six doors from you could’ve done that tattoo, for all you know.

The tattoo journalist interviewing Cartwright in his California home.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the industry is struggling. What do you think will happen to the future of tattooing?

Because the whole world seems to be adapting to the problem with COVID and so forth, I believe tattooing will survive. Still, it’s never going to be the same again because of what people have been forced into, operating behind closed doors, or possibly with limited finances. And the economy being so rotten a lot of people can’t work or even aspire to work and don’t even see any job in the future. So that’s going to limit the amount of money that’s spent on tattoos. Affecting people economically and physically and probably emotionally and mentally. I mean, I don’t personally know of any tattooer that’s committed suicide yet. Still, it wouldn’t surprise me if some around the world have done it. Because if school children are doing it because of the difference in life that they can’t accept—this is real! As we speak, I believe we’re talking about possibly another year of limited meetings…

Every time Cartwright and The Tattoo Journalist meet, they have insightful conversations.

Socializing?

Yes. And so obviously, that’s going to affect the business in many ways. And so I believe the ones that do make it are the “Johnny-come-lately” that don’t even realize the problems they will face, but are so committed to the course that they’re going to figure it out regardless. There will be some who enter the business during this time of trouble, which will likely be okay. But by and large, I would say the industry will never be the same. I believe much more private tattooing will be happening rather than publicly. For sure, if we can’t have any conventions, well, that’s obvious. So I think it’s just going to become such a private enterprise, and tattooers’ lifestyles will change somewhat. They’re going to have to learn to adapt to less popularity and fame.

So it will be more underground.

For sure. It’s already doing that. Many shops have closed permanently and tattooers quite frankly are relying on other skills. A lot of them are going into engraving metal, knives, and guns, or paintings. They’re selling their paintings. Some of them are carvers and sculptors. They are looking for something else to supplement the lifestyle or the income period. I mean, the lifestyle ceases if all you’re doing is going into your studio and molding clay or something, you’re still an artist. It’s just a different medium.

It’s not so exciting for those who enjoyed traveling the world.

Yeah. It’s absolutely going to be a different animal.

B&W photos © Adriana de Barros, the Tattoo Journalist Color Photos courtesy of "Tattoo Man—The Story of Good Time Charlie's”