Having one of Tom French’s paintings hanging in the Scene360 office, clearly means what it means.

We admire what he has envisioned and painted on canvases since 2011—from our first feature of his illusional skull drawings, to present day, his continuous black-and-white oils for solo show “PARALLAX” at Unit London.

He has taken strides to shaping a distinguishable art style, yet through the apparent consistency and meticulousness, he is letting loose with the years—i.e. each brushstroke is more random, fluid, and more of himself in the work.

In this interview we find out why he is so insistent with the theme of mortality and if 19th-century painter Charles Allan Gilbert was an inspiration; what “PARALLAX” is really about, and what his career and life has been like since being a dad.

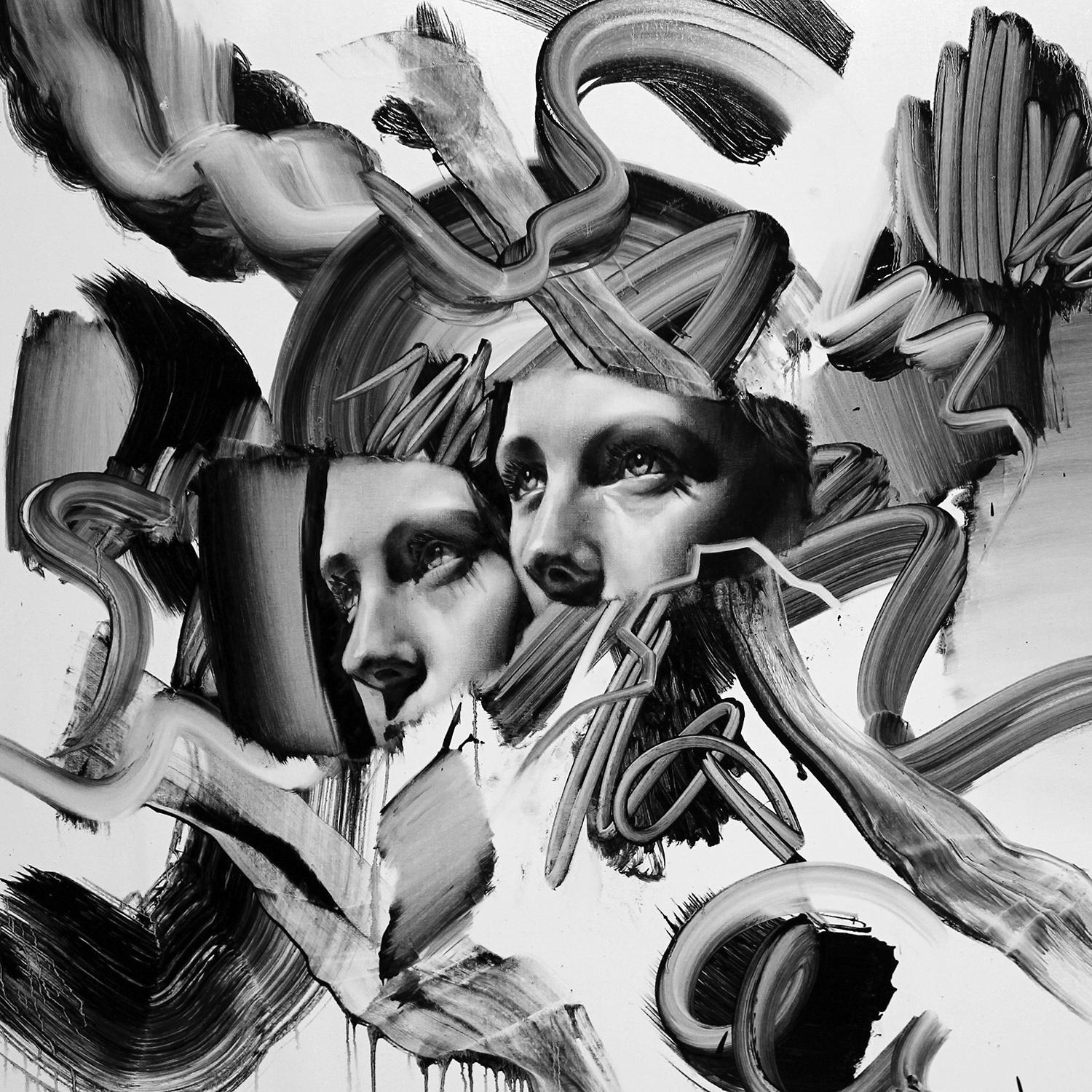

Above: Each painting connects in some way with the other, beautifully cohesive.

Oil paintings part of the series/show, “PARALLAX.”

Has there been a moment (or a specific age) in your life that you thought you would live forever?

I fully intend to—it’s going to plan so far.

Mortality, as you say “the fragility of life” has been depicted quite a lot in your paintings. What has attracted you so much to this subject matter?

It’s not a subject matter that I intentionally pursue, but the work always seems to circle back to it. I’m sure there will be some psychological explanation, but it’s not something I’m fully conscious of.

Mortality is a subject that affects almost everyone, every living thing. We need to live to survive, so our subconscious is programmed to make decisions that will prevent us from dying. Whether we are aware of it or not, this does affect us and our behaviour, which I find fascinating and intriguing. Also, I find that an awareness of our mortality creates a greater appreciation of life and what we have, it makes you want to make the most of it.

These art pieces are best appreciated at a distance to see the full effect of the illusions.

I absolutely love your focus on optical illusions, ambiguous images. Were you initially inspired by Charles Allan Gilbert’s “All is Vanity”?

That image wasn’t a specific inspiration for the series. The series started as I was working on other paintings, and as I stood back or worked very closely I began seeing other images amongst the brushstrokes. I later learned that this is a specific phenomenon called “Apophenia,” similar to seeing objects in the shapes of clouds. So I started working up these apparitions within the paintings, and then moved on to intentionally create the double image/illusion paintings which your familiar with. It was a very natural and fluid process. Once the technique was figured out I was able to align the concepts with the imagery.

As a child I owned a book of paintings by Dali, I think it was my first art book. At a young age I just couldn’t figure out how the illusion paintings were created, it was completely magical, and that feeling has definitely stuck.

How challenging is it to create these optical illusion portraits?

Very challenging! It’s almost impossible to view both images at the same time, your mind jumps from one to the other. The process of creating them is very mentally intense for this reason. And then there’s the technical difficulty—simply getting black and white pigment to look simultaneously like two separate images is a challenge in its-self. I use a mirror to view the paintings in reverse during the process, the image being flipped is the closest you can get to viewing it afresh—something that I find is much needed for such a technical task.

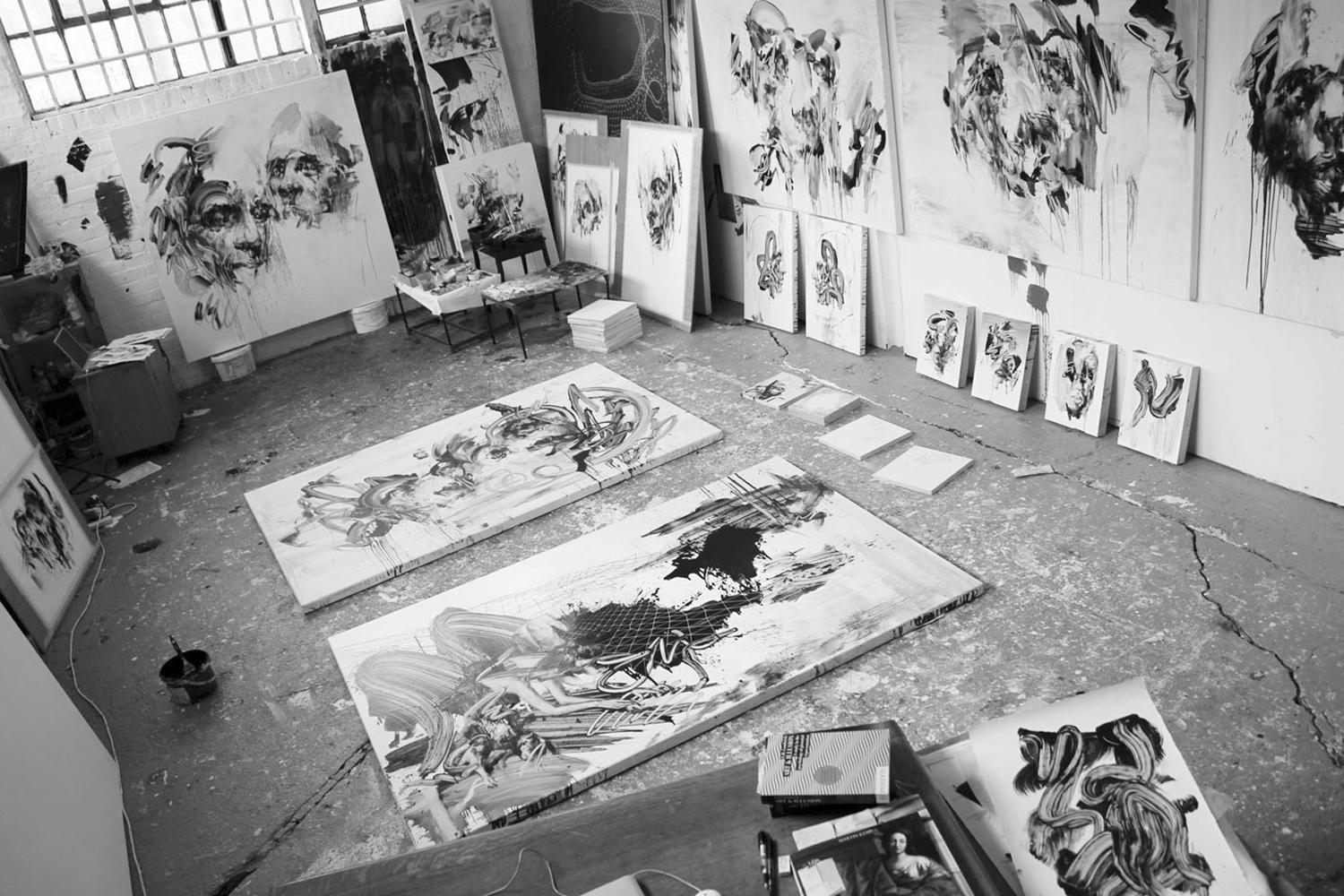

A peek at Tom French’s studio, and below two versions of the composition titled “Align.” (We have the black version).

I have “Align” strikingly displayed in the Scene360 office. I hadn’t realized you did two versions of the painting: 1) in white background and 2) black background. Were you doing tests to see how the portrait would look? How important is it using black and white pigments in your creations?

There are many aspects to black and white images which I find appealing—it’s fascinating that such complex ideas can be visualised using such simple tools as light and dark.

I don’t feel that the images I’m currently creating would benefit from the addition of colour, and that doing so would run the risk of overcomplicating matters; also, colour is by nature unavoidably subjective, so removing this from the equation allows me to bring a greater level of clarity and consistency, both aesthetically and theoretically.

It’s often the case that the use of monochrome reinforces the idea that my figures represent aspects of the mind rather than physical reality—for example, depictions of memory in cinema are often shown without colour to differentiate them from reality. In fact, black-and-white imagery often has a cinematic quality, which suits the idea that the characters are acting out scenes within the paintings.

I find life in general can be very busy, and often cluttered with the unnecessary, so my studio with its vast monochrome canvasses feels like some kind of refuge. Maybe this is just me, but hopefully when the work is exhibited it also acts as some kind of relief from everyday oversaturation.

Your brushstrokes seem to be getting more fluid and abstract as time has moved on. Are you improvising more as you paint in recent years?

Absolutely. In the past I’ve planned my paintings quite meticulously, but for me that way of working becomes restrictive over time, so now the process is much more fluid, and all the more enjoyable for it.

My initial approach to a painting is very fast paced and immediate, I begin with the biggest and boldest abstract marks, working out the overall composition as intuitively as possible. This abstract beginning largely dictates the position of the various elements to follow, allowing the image to naturally progress, harnessing as much of the unplanned/unexpected marks in order to retain a strong sense of immediacy. The process gets progressively less animated as the image develops, with the final stages being a very time intensive process of rendering the technical figurative elements and balancing the lights and darks in order for the structure of the image to pull together as whole. Working this way creates wonderful visual contrast and tension, with technically rendered sections submerged within the free-flowing immediacy of abstraction, reflecting the relationship between the figures and the environment in which they sit.

A mix of photorealism and abstractism in the work of the Englishman.

In your 2017 canvases there is a graffiti-type-of-vibe with classical-style figure studies. Please explain about the actual direction of your new work?

In these latest works, the figures, are presented with photographic clarity, suspended within the ambiguity of abstract forms —reflecting a psychological rather than material space. The figures are made up from a synthesis of snapshots—a free-form chronophotography that substitutes shifting perspectives for motion, these fragments of characters are representative of the way we perceive, visually. When looking at a figure, we do not see it as a whole; our eye moves around, shifting focus onto various points of interest, building up a sensory collage from many images that are ordered and rationalised by the brain. These works chart that mental landscape, the permutational narratives of the visual cortex: the stories told at the shadowy junction of the conscious and unconscious mind.

Its taken a long time to prepare and is my largest exhibition to date. I began working on these new paintings alongside the “Duality” (illusion) series which was discussed earlier, so the new work is a natural progression of the concepts explored in the previous series. Some of these new pieces were started over two years ago and have been gradually added to, others were started after my previous exhibition and have been intensively worked during the preparations.

“PARALLAX” is the name of your recent art show at Unit London. What is about?

The title “PARALLAX” can be defined as the apparent displacement—or difference in the apparent position—of an object caused by a change in the position from which it is viewed. So the paintings explore the literal, metaphorical and metaphysical manifestations of perspective and visual perception. There are underlying narratives throughout the series, with these narratives being explored from various perspectives creating a myriad of different interpretations.

The exhibition is showing at the Unit London from June 1st to June 17th.

The walls and floor of French’s studio is visually appealing and complements the display of his work.

Is it important taking breaks from art making throughout the year?

Very much so, although I don’t take as many breaks as I probably should. The process of creating paintings, particularly a full exhibition is immersive. It’s preferable for all the paintings in an exhibition to work as a cohesive whole, interacting with each other to create something larger than their individual parts. It is somewhat like piecing together a very complex jigsaw, so I find it’s best to take breaks once a large section of the work has been completed; if I have a timeout half-way through I find I’ve lost sight of how the puzzle all fits together.

Define your life as being an artist but also a dad.

It’s taken a lot of adjustment, before being a dad I could be in the studio as and when I liked, work right through the night or whatever hours were required. Now that’s all changed, my time in the studio is very important, but my time with my daughter is more precious, so I need to be much more organised and structured in order to get the most out of both. I’ve learned to switch off the creative obsessive side of my brain when I leave the studio, but I’ve also learned to switch it back on a lot faster when it’s time to work. My partner—Teresa Duck—is also a painter, so we juggle the bulk of the childcare/studio time around whoever’s exhibition is approaching the fastest.

Follow Tom French on Instagram or go to his website.

Images © Tom French